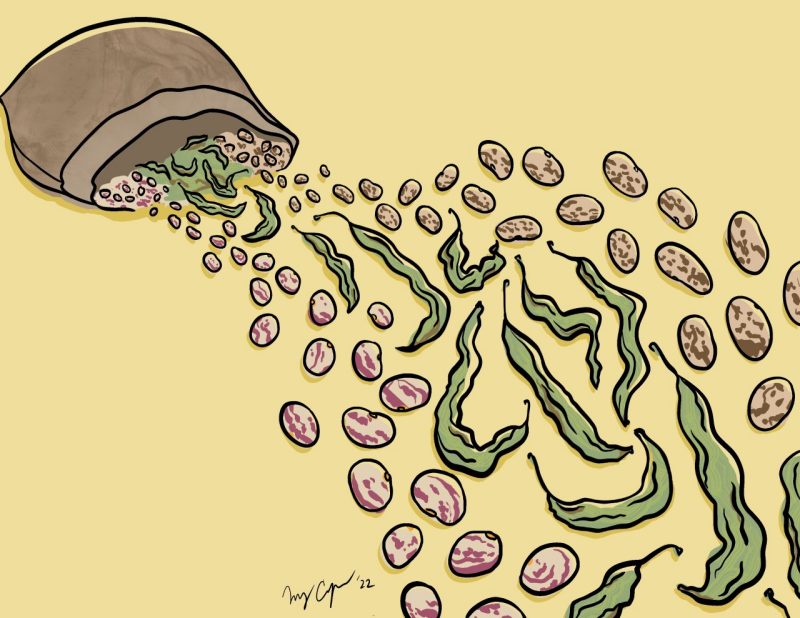

Spilling the beans on a traditional staple of Appalachian cuisine

March 7, 2022

Row by row and seed by seed. That’s how Victoria Ferguson remembers her childhood growing up in a coal camp in the heart of Appalachia.

By age 5, she was in the garden, watching as her father walked the land, using a special tool to dig tiny wells. She and her siblings followed along, working together to plant, cover, and water beans. She recalls her mother’s words to her: “Honey, during the time of the dogwoods, you start to plant.”

Ferguson, interim director of the American Indian and Indigenous Community Center at Virginia Tech, was born and raised in West Virginia. Like many others in the region, her family harvested and dried beans to sustain themselves through mountain winters.

She refers to beans as a “second sister,” because her family planted the crop alongside corn, or the “first sister.” After the corn plants reached “wrist to middle finger” in height, she knew it was time to plant the companion crop. Beans provide nitrogen-rich soil for the corn plants, while the corn offers a trellis for the beans.

Today, despite easier access to chest freezers, home canning, and store-bought foods, dried beans remain a beloved tradition throughout central Appalachia. Ferguson and Asheville, N.C.-based chef Ashleigh Shanti were panelists during a Virginia Tech Humanities Week event in February, “Fall Beans, Shucky Beans, Soup Beans: Perspectives in Song and Story.”

The discussion focused on how beans are grown, harvested, prepared, preserved, and shared throughout the southern mountains. “Shucky beans,” or “leather britches,” are green beans strung with needle and thread, dried, and then rehydrated in their pods while cooking; “soup beans” are shelled pintos slow cooked with salt, pepper, and seasoning meat.

Danille Elise Christensen, an assistant professor in Virginia Tech’s Department of Religion and Culture, facilitated the conversation. She is a folklorist affiliated with the Food Studies Program, the Appalachian studies program, and the graduate program in material culture and public humanities, all at Virginia Tech.

Christensen said dried “fall” beans were an obvious choice to ground an interdisciplinary proposal for Humanities Week, a series of events that illustrated how the humanities enrich and connect our world. The week — sponsored by the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences — was the major focal point of the college’s highlight month for the Virginia Tech Sesquicentennial Celebration. Christensen used clips of songs to introduce a thematic focus for each segment of the tripartite discussion.

“I started brainstorming songs — like ‘Cornbread and Butterbeans,’ or the fiddle tune ‘Leather Britches’ — that show how beans offer a space for cultural commentary within popular expressive culture,” she said.

According to Christensen, the knowledge involved in growing and preparing beans ties together historically dominant populations in Appalachia, including those of Indigenous, African, and European descents.

“Within that large stream of tradition, there is so much interesting variation in the way people have selected bean varieties that exhibit the characteristics they really value,” she said. “We’re looking at the ways that values are made material in these actual objects and in the practices associated with them.”

Shanti, with a bag of dried Sandy Mush greasy beans in tow, said it feels like she has been snapping beans since “before she could walk.” She reminisced about summers spent threading and hanging beans along her aunt’s porch near Danville. As a board member of the Utopian Seed Project, a nonprofit devoted to supporting regional biodiversity, Shanti is passionate about diversifying agriculture and preserving heirloom seeds.

Her culinary training inspired her to create dishes like “buttermilk britches,” which she describes as “the green bean casserole of your dreams.” But, according to Shanti, there is nothing better than a simple bowl of beans. When she serves up “the perfect beans, that have the perfect story, that have been in the perfect conditions,” she feels pride.

“In the same way these Michelin-star chefs have their ingredient worship, we in the South have it too. It just needs to be recognized,” she said. “We love our ingredients. We love our farmers and we do really great work to ensure these crops are preserved.”

Ferguson said while she was growing up, wealthier communities shamed others for eating a pot of brown beans, because they considered it “poor folks’ food.”

“I think we should try hard to change the social attitudes toward beans, because they are so good for you between the fiber and the nutrients,” Ferguson remarked. A dietician, she spent years working as an historical interpreter of Monacan foodways at Natural Bridge State Park. “You can’t beat a bowl of good, regular beans.”

Ferguson and Shanti could not let the event end without sharing preparation tips. Ferguson pleaded with the audience to never, ever pour cold water onto beans that have already started cooking. Meanwhile, Shanti passionately exclaimed that beans should “never be al dente”: only when they can easily be “smashed against the roof of your mouth” have they finished cooking.

“A bowl of beans can be so transformative, and I personally feel like that’s enough,” Shanti said of the Appalachian staple. “People want me to argue that and fight for it, but I think when it comes to nostalgia and food, that’s all people want.”

Written by Kelsey Bartlett