Plaza to honor first Black Virginia Tech employee, family

August 24, 2021

Look to the trees.

On the campus of Virginia Tech, you’ll find mighty pine and sycamore. Thick magnolia and beech. Bountiful oak and walnut.

Thousands of trees beautify the sprawling campus. Some are youthful, planted just weeks ago. Others have swayed in Virginia winds since the 19th century.

Glorious trees.

Even the oldest are still infants compared to the Blue Ridge and Allegheny Mountains. But they are more than relics. They’ve borne witness to history, ascending and branching in step with a bourgeoning university.

Nearly 150 years ago, Andrew Jackson Oliver helped plant the seeds.

He worked as a janitor on campus, where he lived with his wife, Fannie Vaughn Oliver, and their family. Some of the first trees on school grounds grew from seeds planted by Oliver.

But he could never enroll in the school he helped build. He was forbidden for one overarching reason: the color of his skin.

Oliver is the first known Black employee at Virginia Tech.

Born a slave, Oliver began working at the university — then called the Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College — when it opened in the 1870s. The campus was built on land that originally belonged to Native Americans and was later worked by people who were enslaved.

The school hired four more Black people by the end of 1880 to assist Oliver in the school’s every-day activities, according to Virginia Tech’s Black History Timeline.

In a tribute to the Oliver family, the Virginia Tech Board of Visitors approved a resolution to name the plaza at the entrance of the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences building the Vaughn-Oliver Plaza. The naming of the plaza came after a formal nomination by the college.

Located at 200 Stanger Street next to the Upper Quad, the college’s main administrative building stands adjacent to the Blacksburg neighborhood called New Town. The neighborhood was home to many Black men and women who worked at the university between 1880 and 1960.

The board named the plaza for the Olivers in recognition of the family’s time, service, and influence to the history of the university. By extension, the Vaughn-Oliver Plaza honors the local Black community whose members often significantly contributed to the university but rarely received recognition.

Andrew Jackson Oliver was born in 1837. He was enslaved by members of the family for which the town of Blacksburg is named, according to research compiled by Juan Pacheco, a 2019 graduate in psychology. Pacheco published an article about the Oliver family as a student employee in the University Libraries Special Collections and University Archives.

Freed after the Civil War, Oliver helped maintain the campus of the land-grant military institute. Census records indicate Oliver’s sole occupation in 1880 was “janitor VA+MC.”

Oliver and Fannie Vaughn Oliver — also born a slave — married in 1859 and over the next 20 years had at least seven children: Robert, Andrew, Caroline, Richard, Daniel, William, and Essie.

On campus, the Olivers likely resided near the current location of Randolph Hall, according to Pacheco’s research.

Vaughn Oliver was the daughter of Abraham Vaughn, who belonged to a large family with an important history in the Black community, according to Daniel Thorp, a professor in the Department of History and an expert on Black history in Montgomery County.

The Vaughn family includes Vaughn Oliver’s uncle, Gilbert, who was one of the many Black residents of New Town. Gilbert Street in Blacksburg is named for him.

While Andrew Oliver broke a barrier as the first Black employee at Virginia Tech, one of the Oliver sons broke another.

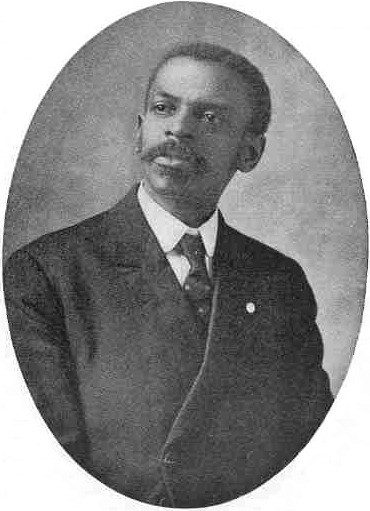

Andrew “A.J.” Oliver Jr. was born to Andrew Sr. and Fannie Vaughn Oliver in 1862 amid the Civil War. With the support of his parents, he earned an education from Christiansburg Industrial Institute, according to Pacheco’s research. The Black secondary school served many Black residents in the New River Valley until 1966.

A.J. Oliver didn’t stray far from his roots. He relocated to West Virginia and worked as a laborer. Within a decade he trained to become a lawyer, according to Thorp.

In 1887, A.J. Oliver became the first Black person admitted to the bar in West Virginia. Two years later, he moved to Roanoke and is believed to be the city’s first barred Black attorney. He was also a prominent member of the local Black community.

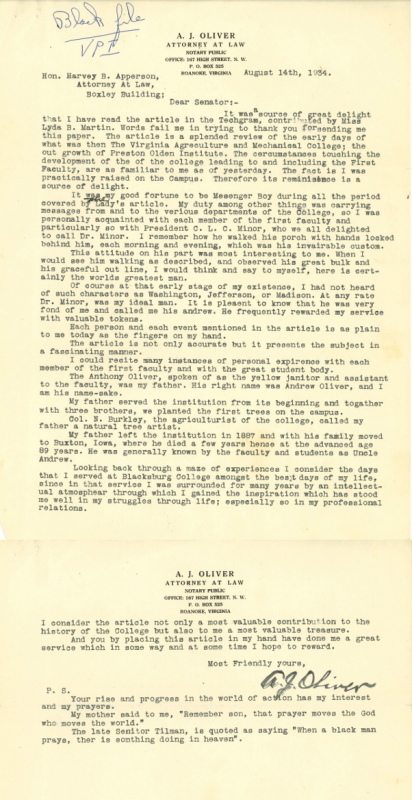

From his law office in Roanoke, A.J. Oliver wrote a letter dated Aug. 14, 1934, in which he reflected on his father and his childhood spent on the campus of what is now Virginia Tech. He wrote the letter in response to an article by Isaac Diggs, an 1880 graduate, in Techgram, the university’s old alumni newspaper. The article and letter are referenced in Pacheco’s research.

Diggs had mentioned Oliver Sr. in his article titled “The First Faculty.”

In his response to the article, A.J. Oliver wrote that he, too, worked on campus with his father.

“The fact is I was practically raised on the Campus,” A.J. Oliver wrote. “Looking back through a maze of experiences I consider the days that I served at Blacksburg College amongst the best days of my life.”

A.J. Oliver explained that Oliver Sr. served the institution from its origin and that he and his three brothers helped their father plant the first trees on campus.

The school’s agriculturist called his father “a natural tree artist,” A.J. Oliver wrote.

In the 1880s, the Oliver family left Blacksburg for Iowa. Citing Michael A. Cooke’s “Race Relations in Montgomery County, Virginia 1870-1990,” Pacheco described the possible reason for the family’s departure.

Representatives from a coal-mining company had traveled to the South to recruit Black workers. The businessmen offered free transportation and $10 per week, doubling the average weekly pay in Montgomery County. “This led to what Cooke referred to as a ‘Black exodus’ in the New River Valley,” Pacheco wrote.

Oliver worked in the mines and later resumed janitorial duties as he lived the rest of his life in Iowa communities.

Census data in 1920 lists Oliver at age 82 as living in Monroe County, Iowa, with son Richard, daughter-in-law Rosa, and grandson Osea, according to Pacheco’s article. Oliver died at age 89.

On a visit to campus, the Virginia Tech community can look to the plaza as a reminder of the contributions made by the Oliver family and the many fellow Black people who helped build the university.

But the Oliver family’s presence can be felt beyond the plaza and almost anywhere on campus.

Just look to the trees.

Written by Andrew Adkins