Gary Downey receives Society for Social Studies of Science’s Infrastructure Award

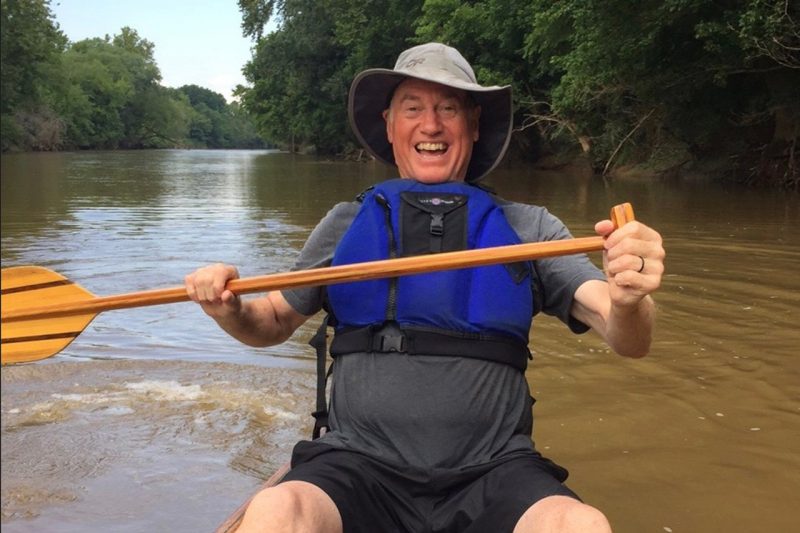

The oar gently passages through the water and moves the canoe forward. Gary Downey is in charge of this vessel, expertly steering from the back. This philosophy is how he approaches leadership in general.

“Great scholarship,” said Gary Downey, Alumni Distinguished Professor of Science, Technology, and Society at Virginia Tech, “includes making knowledge travel into the world to challenge settled ideas and practices.” The Society for Social Studies of Science championed this view when it named him the first individual scholar to receive its Infrastructure Award.

For Downey, the award honors his achievements building scholarly infrastructures that have advanced his field of science, technology, and society.

He arrived at Virginia Tech in 1983 to help build the graduate program in science and technology studies, after helping to build a related undergraduate program at Michigan Tech. He brought with him a boundary-pushing idea — the notion that engineers could someday become leaders in anticipating and addressing the social implications and effects of new technologies.

His interest in engineering stems from his childhood in Pittsburgh. Downey’s generation was among the first to seek college degrees rather than work in the steel mills. Going into engineering seemed an effective path from a blue-collar career to a white-collar one. But, he later realized, this notion seemed to apply only to males. If engineering work was considered “men’s work,” it somehow must be influenced by society. This implication fascinated him.

As an undergraduate at Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, he found his interest piqued by environmental disputes involving nuclear power and pollution. His engineering background allowed him to understand the technical aspects of the controversies. What he could not fathom, though, was how people came to disagree, take different sides, and fight over these issues.

To understand the different viewpoints, Downey began taking classes in anthropology and linguistics. He then discovered a defunct five-year program where he could study both the sciences and humanities. He persuaded administrators to let him pursue this opportunity, earning bachelor’s degrees in both mechanical engineering and social relations.

From there, Downey’s master’s and doctoral degrees at the University of Chicago challenged the boundaries of cultural anthropology as he studied groups opposed to nuclear power in the United States. His long-term interest remained the work and identities of engineers.

“I became an anthropologist,” Downey said, “to figure out something that my engineering education had left out: how engineers might appreciate and learn to work effectively with people who think differently than they do.”

Then he discovered and joined the new field of science, technology, and society. It provided an opportunity to experiment with the kind of engaged scholarship that he hoped to develop. In the 1990s, he began calling it critical participation.

“In a university setting,” he said, “you have scientists and engineers who study the technical dimensions of issues involved in science and technology, and then you have social scientists who study the social dimensions. But neither studies the other. Our graduate program at Virginia Tech is unique because it trains scholars and practitioners to look at both at the same time, including how they change over time.”

With his interest in the study of engineering, he discovered he was not alone.

“I realized there are people like me, worldwide, interested in engineers and engineering,” Downey said. “So I thought, let’s bring them together. In 2003, the Society for Social Studies of Science and the Society for the History of Technology happened to have a joint meeting. I figured this would be where the most scholars interested in engineering would be present.”

He posted a sign advertising a breakfast meeting. Nineteen people showed up.

The following year Downey found himself in Paris. At the joint meeting between his society and the European Association for the Study of Science and Technology, he and others launched the International Network for Engineering Studies. He felt Paris was meaningful because it was there, historically, that engineering first emerged as a definable field.

Fast forward to Sept. 2019, at the Society for Social Studies of Science’s annual conference in New Orleans. While enjoying a reception that included a band and dancing, Downey, the past president of the society, found himself on the dance floor when the awards ceremony began. The music stopped. When the president announced the Infrastructure Award, he alone went to receive it. For the previous three years, the award winners had all been teams or organizations. Before the award committee had notified him, he had not known he was even a nominee.

The committee honored Downey for his leadership and creativity in developing scholarly infrastructures that express science, technology, and society knowledge and commitments, and enable these to engage worlds beyond the academy. The Infrastructure Award acknowledges his contributions to Virginia Tech and in building a new scholarly field, as well as his leadership in a recent initiative that members responding to a survey called the most exciting new development in the society.

While co-founding and co-nurturing the graduate program of the Department of Science, Technology, and Society, he worked to build scholarly infrastructures for engineering studies, to both study engineering and participate critically in it. He co-founded and edited for a decade an indexed journal, Engineering Studies, and founded a capstone book series published by MIT Press.

In addition, he established a book series that produces digital publications and licenses them to universities so students can have free access. One he coauthored, “Engineers for Korea,” was named a 2017 Sejong Book by a scholarly committee convened by the Korean Ministry of Culture. The award honors books thought to have high value as academic texts and improve the public’s reading culture. The ministry paid to distribute the book throughout Korean schools, universities, and libraries.

To facilitate direct participation in engineering, Downey led a process to expand the Liberal Education Division of the American Society for Engineering Education to include “Engineering in Society.” And he created a multimedia version of his popular course, Engineering Cultures, a frontline effort to help students learn to reflect critically on their knowledge, identities, and commitments.

Beginning in 2014, Downey led the founding and continues to build a scholarly movement called STS Making and Doing, highlighted by a program at the annual meeting and a forthcoming book. This movement theorizes and enacts practices of engaged science, technology, and science scholarship. It calls particular attention to ways of expressing knowledge that extend beyond the academic paper or book.

“Downey’s initiatives and reputation have transnational, intergenerational reach, expanding how STS scholarship is conceived so that it can travel beyond the boundaries of the field, challenging and inflecting dominant images and practices of science and technology,” the award committee stated.

But Downey, in his acceptance of the honor, dedicated the award to colleagues who sometimes feel their infrastructural scholarship has been invisible work. These are scholarly leaders, he said, who confront the difficult challenges involved in making science, technology, and society knowledge travel.

“Remember,” he said, “you steer a canoe by paddling from the back.”

Written by Leslie King