Insights of American Soldiers During World War II to Be Made Available

April 30, 2018

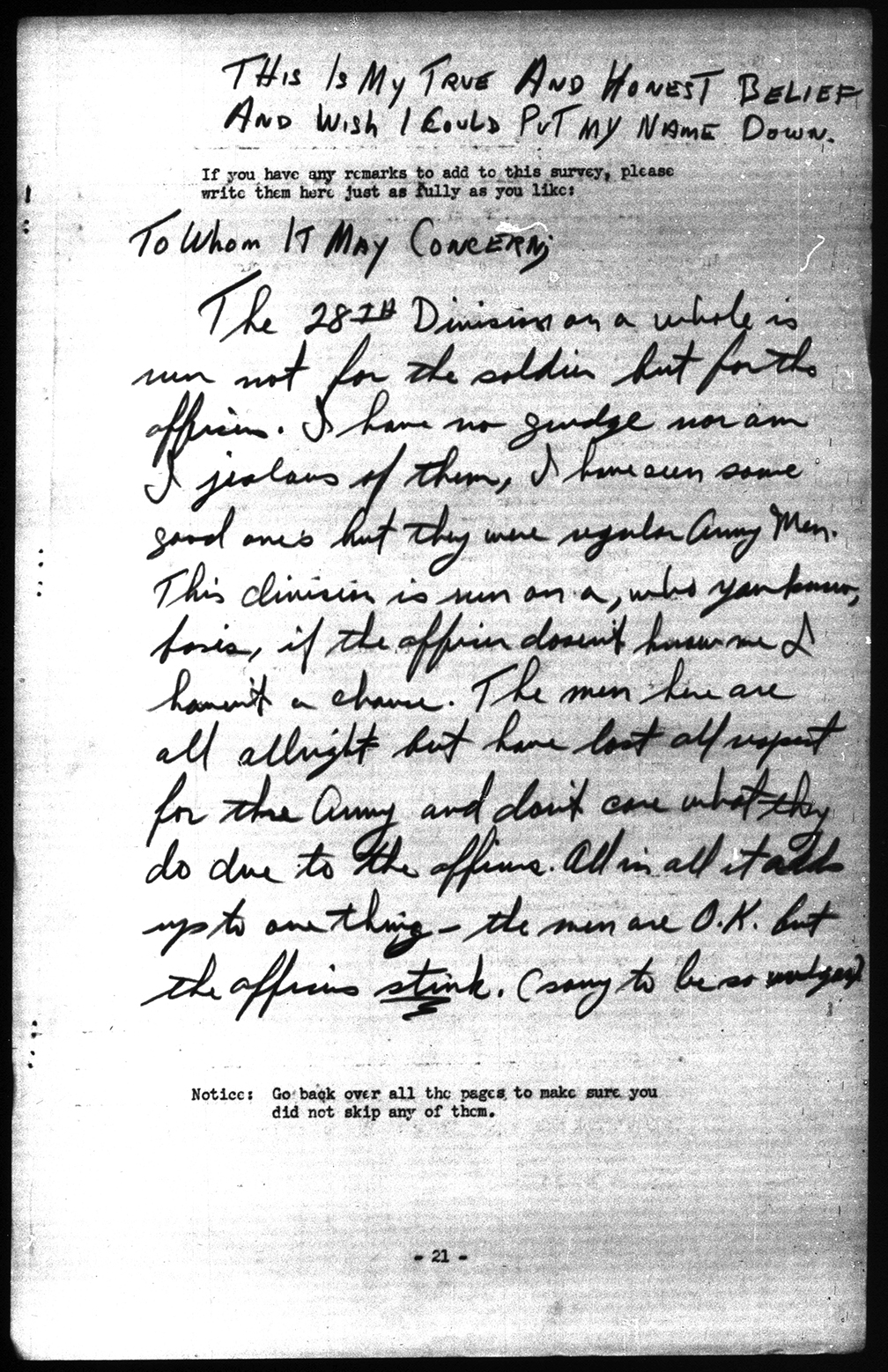

“If an industrial concern were run as the Army is being run, it would be bankrupt in six months,” one U.S. soldier wrote on a World War II survey.

“I think the whole nation should be asked to sacrifice as much as the soldier,” another scrawled.

Still another concluded his handwritten remarks with a vigorous “To hell with Hitler!”

These sentiments are excerpted from just a few of the more than 65,000 entries captured in a remarkable collection of written reflections by U.S. soldiers who fought during the Second World War.

A team of Virginia Tech experts is now poised to bring those narratives to a broad audience through The American Soldier in World War II, a national initiative aimed at using crowdsourcing and natural-language-processing techniques to reconstitute a comprehensive portrait of the largest army in U.S. history.

“This immense collection of World War II reflections provides us an unparalleled view of this monumental conflict from the personal perspective of the American soldier,” said Edward Gitre, the Virginia Tech assistant professor of history who is leading the project. “We are hoping to write — quite literally — tens of thousands of personal expressions of soldiers into the historical record.”

Early in the conflict, the War Department created the Army Research Branch, a social and behavioral sciences unit that surveyed and interviewed approximately half a million soldiers over the course of the war. Participating service members were promised anonymity.

Free from the threat of censorship or retaliation, tens of thousands of those soldiers not only filled out the lengthy surveys, but also provided handwritten commentary.

While the quantitative data were later digitized and are available through the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration and Cornell University’s Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, the comments themselves have long been available only to those who could view them on microfilm rolls on-site at the National Archives building in College Park, Maryland.

As a result, the very personal words of thousands of soldiers have remained largely unread. So, in the spring of 2017, Gitre secured a National Endowment for the Humanities startup grant to create searchable digital archives of the soldiers’ personal, real-time insights into military service. The National Archives has provided support as well, initially through the coordination of the public release of relevant digitized records.

“During World War II, the U.S. Army was a ‘citizen-soldier’ force, as only a fraction of the more than 16 million men and women who served in the Armed Forces had any prior military experience,” said Gitre. “For some, the transition came naturally; others had difficulty.

“These soldiers were eager to offer additional advice, praise, and criticism, and to share their stories of serving in the Army. Their remarks touch on everything from patriotism to morale to such mundane topics as unsavory rations.”

The American Soldier Project, said Kurt Luther, the initiative’s technical director and an assistant professor of computer science in the College of Engineering, is “a researcher’s goldmine into understanding the common soldier’s experience during World War II. The key is to make their words more accessible to scholars and the public. Handwriting is generally hard for computers to read, but humans can be pretty good at it.”

The project team will take advantage of that human skill through a crowdsourced transcription project on Zooniverse, an online citizen-science platform with more than a million registered volunteers.

To help engage the public in capturing those remarks digitally, Virginia Tech will also host a transcribe-a-thon on May 8 — the anniversary of Victory in Europe Day, better known as VE Day — from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. in the Athenaeum of Newman Library. The university is encouraging other sites across the country to participate virtually in the transcribe-a-thon as well.

Once the crowd has transcribed all the soldiers’ handwritten responses, which Gitre predicts will take a year or two, the team’s next task will be to relink that commentary to the multiple-choice survey responses using both human and artificial intelligence to identify salient topics across the collection, with natural-language processing and other innovative computational methods.

The team will then make the reconstituted data accessible to the public and to scholars through an open-access website that will enable exploration of the surveys and responses.

Finally, the team will work with David Hicks, a professor in the Virginia Tech School of Education, to craft lessons for high school teachers and college professors, with the aim of using the handwritten reflections to engage students in primary-source analyses of wartime experiences.

“The U.S. helped the Allies win World War II because thousands of ordinary Americans fought and sacrificed, either on the home front or on the battlefield,” said Luther. “It’s important to understand the experience of these everyday men and women who gave so much for the greater good. This project helps tell the stories of their experiences in their own words.”

The May 8 transcribe-a-thon is hosted by University Libraries in collaboration with the Department of History, the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences, and the Department of Computer Science.

In addition to Gitre and Luther, key project collaborators include Aaron Schroeder, a senior research scientist, and Gizem Korkmaz, a research assistant professor, both in the Social and Decision Analytics Laboratory of the Biocomplexity Institute. Schroeder and Korkmaz will extract data from the survey files and apply artificial intelligence tools to determine collection topics.

Other major Virginia Tech contributors include Nai-Ching Wang, project developer and a doctoral candidate in the Department of Computer Science; Michael Hughes, social science consultant and a professor in the Department of Sociology; and, in University Libraries, Corinne Guimont, digital publishing specialist; Christopher Miller, digital humanities coordinator; Michael Stamper, data visualization designer; Nathaniel Porter, data consultant; and Marc Brodsky, public services archivist.

“‘The American Soldier in World War II’ is a fabulous project and a great fit for Virginia Tech,” said Peter Potter, director of publishing strategy for University Libraries. “At University Libraries, we are particularly gratified to be playing a part because it requires us to draw upon expertise in multiple areas in which we are especially strong, including in the digital humanities, data management, and informatics more broadly. We see this as an opportunity not simply to bring long-hidden records out into the open, but to maximize their usefulness to the largest number of potential users, from scholars and students to anyone in the general public with an interest in America’s crucial role in World War II.”

The National Endowment for the Humanities — a U.S. government agency that provides grants to support research, education, preservation, and public programs in the humanities — has been a significant funder of history and literature projects in the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences, with nearly $1 million in grants in the past six years alone.

In addition to providing digitized records, the National Archives, the country’s official recordkeeper, will be promoting the project to its citizen-archivist community and will ingest completed transcriptions back into the National Archives Catalog.

The Social Science Research Council — an international, independent nonprofit organization — granted the project usage rights to the original research it published in 1949.

Written by Paula Byron