Virginia Tech historians uncover the facts about masks

August 19, 2020

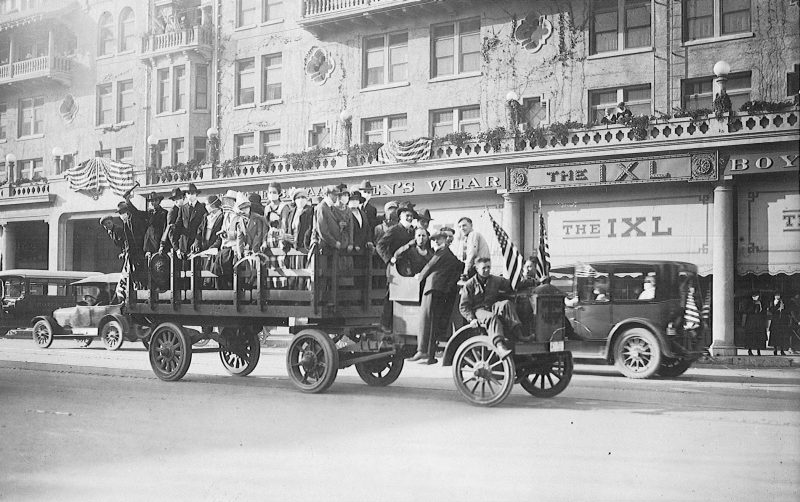

More than 100 years ago, health officials urged Americans to protect their country by wearing masks.

Face coverings help prevent the spread of a deadly flu strain, the experts said.

In response, cities and counties across the nation mandated mask use. Residents could face fines or jail time if they didn’t follow the law in some places.

Flash forward to 2020 and COVID-19. Health experts are again encouraging face coverings to protect against a dangerous virus. In this pandemic, more than 25 states require masks in public.

While millions of Americans have complied with the mandates, some choose to ignore laws and science.

The same scenario played out during the 1918 flu pandemic, according to a team of Virginia Tech historians.

“Although a century divides these two epidemics, mask hesitancy and outright refusal unites them,” said Ariel Ludwig, who earned her Ph.D. in science and technology studies at Virginia Tech.

Ludwig is part of a team of Virginia Tech researchers exploring the use of masks during the 1918 flu pandemic. She’s joined by Jessica Brabble, a master’s student in history, and E. Thomas Ewing, a professor of history.

The Flu Mask research project launched this summer. Sponsors include the Center for Humanities, the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences, and the Department of History.

“This project examines the historical experience of masking during the 1918–1919 flu as a way to understand how people experience a pandemic, how masks fit into a broader public health response, the scientific evidence of the effectiveness of masks, and the lessons learned from this historical experience for future uses of masks, including COVID-19 in 2020,” said Ewing, who serves as associate dean for graduate studies and research in the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences.

Findings from the project have appeared in publications such as HistoryExtra, the BBC history magazine; the Richmond-Times Dispatch; The Roanoke Times; Items, the newsletter of the Social Science Research Council; and the blog of the Society for the History of the Golden Age and Progressive Era.

Brabble, a second-year graduate student, said the team has identified several parallels between mask use in 1918 and today.

“Mandates for workers in 1918 feel familiar,” she said. “Even in areas where the general public was not required to wear masks, many people in specific professions were. Dentists, barbers, food industry workers, and store clerks were frequently required by local health boards to wear masks while serving the public. This is very similar to 2020, where essential workers are required to wear masks on the job.”

Localities across the United States required masks during the 1918 flu pandemic. But unlike today, no statewide orders existed.

Objections from some Americans to flu masks in 1918 sound familiar, too. Americans couldn’t log onto Facebook to voice dissent in comment sections. But they wrote letters to the editor, defied policemen on city streets, defended themselves in court, and in some cases even formed an organized opposition.

In San Francisco, a group of Californians created an “anti-mask league” to protest the city’s mask requirements, Brabble said. League members questioned the effectiveness of masks and the legality of the city ordinance.

“The biggest difference between 1918 and today regarding masks is how long mask mandates lasted,” said Brabble. “Mask mandates during 1918 typically only lasted a few days or a few weeks. By contrast, we’ve been under a mask mandate for a few months now in Virginia.”

Americans faced stiffer punishments for not wearing masks during the 1918 pandemic, Brabble noted.

“Arrests were particularly prominent in California, where thousands of citizens were fined or jailed for violating the masks mandate,” she said. “Some citizens were arrested for forgetting to put their mask on once they stepped out of a restaurant. Others were arrested for outright refusing to wear masks.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, most states and cities have placed the onus on businesses to enforce mask laws. However, some localities, such as Houston, recently announced a $250 fine for anyone not adorning a mask in public spaces.

Ludwig has focused her research primarily on the medical and public health literature addressing the 1918 flu. When examining each pandemic, Ludwig said, it’s important to avoid generalizing based on anecdotal evidence.

“Each pandemic takes place in specific political contexts — one toward the end of World War I, the other in a politically divided nation on the precipice of an election,” said Ludwig.

Studying each pandemic has provided important lessons for the public, the researchers said.

“There are a number of takeaways, but perhaps the most urgent is the recognition that those who are most vulnerable prior to an epidemic are hit the hardest,” said Ludwig. “For instance, the rates of influenza, and now COVID-19, are much higher for those who are incarcerated and unable to protect themselves.”

Brabble, Ewing, and Ludwig have published essays on their findings, including “Masks on Campus: Historical Lessons from 1918 for 2020.” To learn more about the Flu Mask project, visit the research team’s website.

Written by Andrew Adkins