Researchers study how privacy preferences and family tensions can deter use of contact tracing apps

November 13, 2020

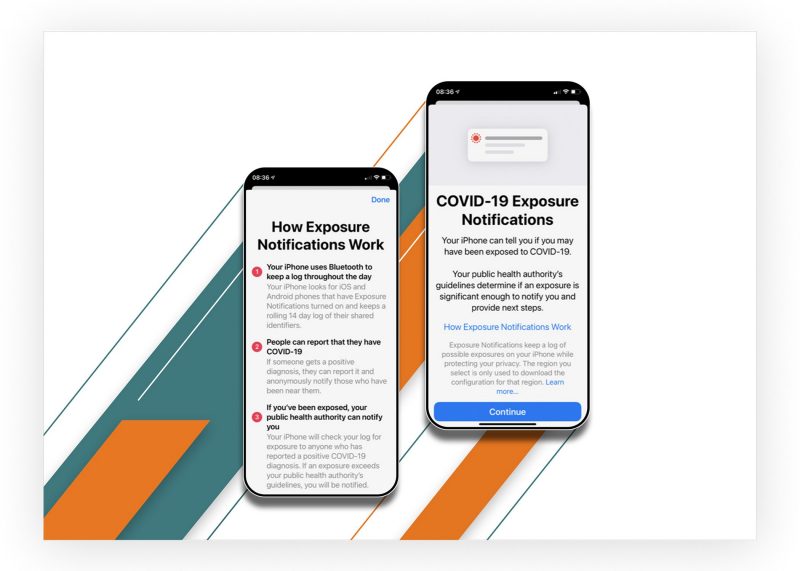

As a tool for controlling the spread of COVID-19, mobile applications for contact tracing are most effective when they are widely adopted and left on indefinitely. But adoption rates of such apps are low, due in part to privacy concerns.

The issue was intriguing for Virginia Tech researchers France Bélanger and Katherine Allen, who were engaged in a study on smart home speakers and the privacy and other concerns they sparked when the pandemic emerged.

Pondering the dilemma of public health officials trying to expand the use of contact tracing apps, the researchers wondered whether such apps also triggered privacy-related tensions within families like those their study found when smart home speakers were introduced.

Bélanger, professor of accounting and information systems in the Pamplin College of Business, and Allen, professor emerita of human development and family science in the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences, completed their smart speakers study and began contemplating the potential applications of that project’s model to the pressing new public health problem that had developed.

With a grant from the National Science Foundation, they launched their new investigation: to understand how individual and family privacy preferences can lead to household tensions and how they can affect adoption of contact tracing apps.

With both smart home speakers and contact tracing apps, Bélanger said, adopting the technology requires privacy decisions — what and how much information to disclose — that involve a combination of individual and family-level considerations of preferences and habits.

Tensions may arise when individual preferences and habits are not compatible with those of other members of the household, Bélanger said. Some family members may feel strongly about their privacy and the control of their data.

With smart phones, Bélanger said, “many people already have a strong opinion on their capabilities and features and how invasive those can be.” People may worry that using contact tracing apps may result in the misuse or sale of their data, she said, especially when the apps are sponsored by the government or by big companies.

“They may fear their location is being tracked or that they may suffer consequences if they are found to have broken COVID-related ordinances or contracted the virus,” Bélanger added.

“Families will have to discuss the perceived risks and benefits of these apps. Any individual decision could affect the entire household. For example, if family members go to dinner together, and one person has contact tracing turned on, the entire family is functionally traced.

“Understanding the concerns and barriers will assist us in providing guidance on how to foster acceptance in families and society as a whole.”

Bélanger noted that studies suggest that such apps are most effective when 80 percent of smartphone users employ them and when contact tracing notifications are turned on indefinitely. Individuals can be promptly informed when they have been exposed and can seek testing and treatment and/or they can self-isolate.

In deciding whether to use a contact tracing app, Bélanger said, families will consider many factors, one of which is the health and vulnerability of other family members.

“A family may choose contact tracing to protect family members with higher health risks, such as being immunocompromised, having other chronic health conditions, or being older.”

Families may also adopt contact tracing if they have members who are essential workers on the frontlines of the pandemic — doctors, nurses, or grocery-store employees, for example.

Their research, Bélanger said, also applies to other social units, such as roommates and “pods” — small groups of people who interact closely but who are committed to following COVID-19 safety measure to safeguard each other’s health.

The pilot testing stage of the project primarily surveyed pairs of roommates. Now under way is a survey of pairs of parents and their teenagers that includes questions about the pandemic and its effects on them, the challenges their family faces, and the parent-teen relationship as well as questions about privacy and information disclosure, identity theft and fraud, and awareness of contact tracing apps.

The same parent-teen pairs will be surveyed again in early January to learn how the families have coped with contact tracing and modified their decision-making.

Bélanger expects to find differences between parents and teens in reporting on some aspects of their family experience as well as differences that reflect political affiliation or the health status of family members and varying levels of awareness and knowledge about contact tracing apps.

“We hope to then develop a model of decision-making about contact tracing use and information disclosure as a result of the resolution, or not, of these within-family tensions.”

Recalling their earlier work, Bélanger said: “The smart home speaker study heavily informed our current project. It gave us insight into the process that occurs when a new technology is introduced in families. But as privacy decisions and behaviors can change over time with new information, we expect to refine this process model with our latest study of contact tracing.”

On the research team with Bélanger and Allen are Robert Crossler, a faculty member at Washington State University who earned his Ph.D. in accounting and information systems at Virginia Tech; Jessica Resor, a doctoral candidate in human development and family science; and Travis Finch, an undergraduate statistics major with a minor in national security and foreign affairs.

Their team is one of three at Virginia Tech that recently received RAPID grants from the National Science Foundation on the social implications of COVID-19.

Written by Sookhan Ho