Virginia Tech students find timely parallels between the coronavirus pandemic and the 1918 influenza pandemic

May 29, 2020

Ending social distancing too quickly during a devastating pandemic caused death rates to increase in parts of the United States, prompting additional rounds of restrictions.

In some smaller cities, the second wave of the outbreak caused more deaths than the first.

Counties with low populations reported a higher death rate than large counties in certain states.

The year: 1918.

The research team: undergraduates at Virginia Tech.

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the students delivered in-depth research on the country’s experience with the 1918 influenza pandemic through a collaborative presentation with the National Library of Medicine as part of the library’s ongoing collaboration with the National Endowment for the Humanities on research, education, and career initiatives.

“Reporting, Recording, and Remembering the 1918 Influenza Epidemic” streamed live April 29 on the National Institutes of Health website, where it’s now available for viewing.

In the videocast, students in “Topics in History of Data in Social Context” — taught by E. Thomas Ewing, a professor of history at Virginia Tech — articulated several lessons from 1918 that are pertinent to the current global health crisis.

The class split into three groups to deliver findings on the messaging used in news coverage, the effectiveness of social distancing, and how communities recovered in the flu’s aftermath. Data from newspapers came directly from the Library of Congress’ “Chronicling America” catalog.

Through empathetic lenses, students pored over newspaper articles from both large and small publications along with statistics on caseloads and deaths.

Group One consisted of Ian Gardiner, a junior majoring in chemical engineering; Louisa Glazunova, a junior majoring in communicating science and social inquiry; and two computational modeling and data analytics majors — Emily Swanson, a senior, and Fiona Tran, a junior.

For most of the fall of 1918, the students found, news coverage revolved around the flu despite the ongoing events of World War I.

The team articulated the tone of newspaper reporting in a dozen U.S. cities throughout the course of the epidemic, including during the apex, which lasted from late September to early November. States represented in the research included Florida, Indiana, Kansas, Maryland, Missouri, North Carolina, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, and West Virginia.

“Initially, we found that each city had examples of flashy or alarming headlines that created a panic,” said Glazunova. “As the pandemic started to worsen, headlines began taking more of a calm and relaxed tone.”

To illustrate the types of rhetoric used in the newspapers, the students created a word cloud in the form of a hand. The larger the word, the more frequent the newspapers used them in daily coverage. Terms that appeared most often included “panic,” “epidemic,” “death,” “doctors,” and “quarantine.”

Tran said the group found many instances of headlines comparing the epidemic to the war, based on the death toll. Other headlines offered more reassurance, such as “Don’t Be Alarmed.” A headline from Salem, Massachusetts, for example, read “No Influenza Cases Reported in Salem: If You Don’t Want it, Keep Away From Crowds — If You Get It, Go To Bed.”

Group Two focused on the effectiveness of social distancing in Missouri and Indiana, states that had similar population data and experienced caseloads and death rates on par with the national average. Members of that group included Jacob Beachley, a junior majoring in history; Yash Joshi, a senior majoring in computational modeling and data analytics; Matthew Mirabella, a freshman majoring in university studies; and Connor O’Hanlon, a sophomore majoring in aerospace engineering.

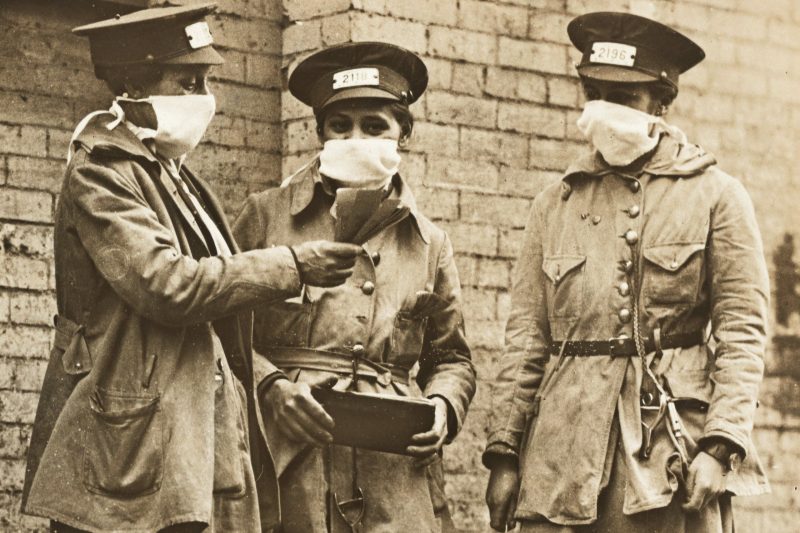

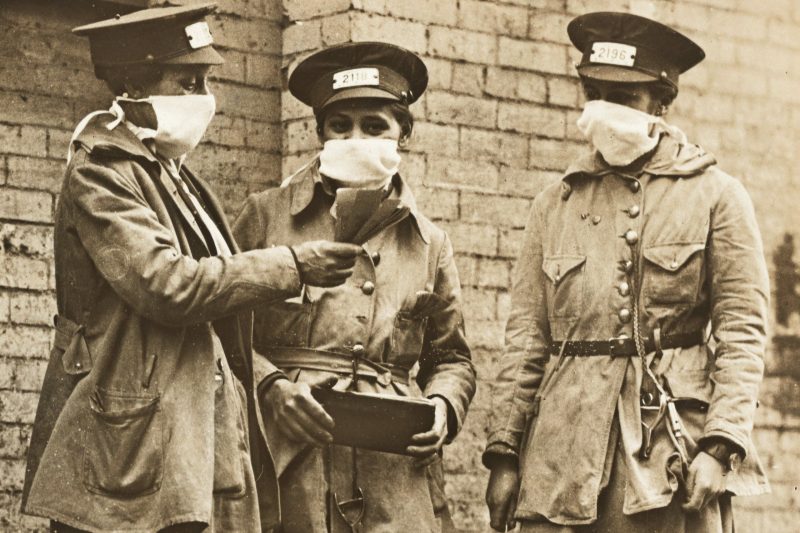

Like today, measures to prevent the spread of virus included the closing of schools, churches, theaters, bars, and other public gathering sites. Some cities required masks in public. The students found some examples of cities and counties imposing measures more quickly than states.

Butler County, Indiana, for example, issued closing orders on Oct. 10.

“We see here that as the flu started to get bad, these localities are starting to take action sooner than the states have,” said Beachley.

Joshi said the student researchers studied county-level data with the notion that a higher population should correlate with an increased number of total deaths.

But that wasn’t the case. The most populous county — Marion County, with a population of 318,000 — had only the sixth highest death rate. Meanwhile, Newton County, Indiana, had the 87th highest population, with 10,549 residents, but the highest death rate of all Indiana counties in October 1918.

“We wanted to hone in and ask the question, is this because of a lack of medical attention, or a lack of social distancing measures throughout the counties?” said Joshi. Counties with high death rates included many counties with small populations. “This is concerning because we expected social distancing throughout the state in one uniform order. However, this wasn’t the case at all.”

Beachley displayed a news clipping from October 1918 in Lake County, Indiana. The county experienced an influenza death rate of 18.38 per 10,000 that month.

In the news article, the headline read “No Gatherings of Any Kind Allowed: Lake County Health Officer Says Influenza Situation Is Still Very Serious.” Beachley said the story provided an example of citizens not abiding by guidelines.

“They have guidelines for no political meetings, no public gatherings of any kind,” said Beachley. “But it says in the clipping that thoughtless individuals made it hard for them to enforce the orders. People are making an effort to open theaters. Some people are even going to funerals claiming a relationship to the deceased. That definitely played a role in Lake County’s significantly higher influenza rate.”

Beachley, Mirabella, and Joshi also found articles from both Indiana and Missouri in late November detailing how caseloads increased after the state relaxed social distancing guidelines, prompting a return of distancing orders.

“We found that social distancing does lower the total infection rates and death totals,” said Joshi. “To go deeper into that point, it’s not just social distancing. It’s also proper enforcement. … Whenever it was mandatory to wear masks in public, to limit social gatherings, this is where we see the death rates were lowering and the cases were lowering as well.”

In Group Three, junior history major Miguel Alvarez, sophomore computational modeling and data analytics major Katie Kromer, sophomore electrical engineering major Alessia Scotto di Luzio, and sophomore public health major Stephanie Valencic focused on the second wave of outbreaks and the recovery process in six U.S. cities during the crisis.

For each of the cities — located in Florida, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia — the first wave and public gathering bans started in October. By late November, some cities began lifting restrictions.

Wheeling, West Virginia, experienced a second wave starting Dec. 3. The other cities felt the resurgence over the following weeks into mid-January.

In Salem, Oregon, the second wave proved shorter but the increasing number of cases and deaths prompted the city health department to resume social distancing policies, including the closing of schools.

By Feb. 10, the cities stopped seeing cases of the flu.

“Some of the commentary seen from the newspapers shows how life was affected by the pandemic, even after it was over,” said Scotto di Luzio.

One article emphasized that 50,000 children became orphans as a result of the flu.

“This makes us realize that even after the flu was gone,” said Scotto di Luzio, “it couldn’t just be forgotten and things could not just go back to normal because life was completely changed for a lot of people due to the pandemic, including these children who lost their parents.”

Alvarez, Kromer, Scotto di Luzio, and Valencic also studied how attention to the flu shifted after the pandemic ended. Within two months, newspapers had resumed covering the war with little mention of the flu.

To conclude the group’s presentation on the nation’s recovery, Kromer provided significant takeaways from “American Pandemic: The Lost Worlds of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic,” a book by historian Nancy Bristow, who participated in the videocast. Mistakes were made throughout the nation to control the spread of the virus, but the strong will and optimism of health professionals is also worthy of remembrance, Kromer said.

“We cannot be quick to forget the devastation that influenza had during 1918 and 1919,” said Kromer, “not only to those who died, but to those who were affected mentally and emotionally.”

The group listed parallels and differences to COVID-19 to the 1918 flu. Similarities include false claims of medication options to cure the illness, the group found.

Following the presentation, the students answered questions submitted by livestream viewers through Twitter and email.

The historians participating in the videocast lauded the students for their deep dive during the symposium.

“I’m impressed by the research questions, careful methodological questions, and the findings that have such significance for us at this moment,” Bristow told the students. “You’ve demonstrated beautifully that history matters, and we can learn a great deal by crunching numbers.”

The students received additional feedback from Ewing; Jeffrey Reznick, chief of the History of Medicine Division of the National Library of Medicine; David Morens, senior scientific advisor for the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases; and Deborah Thomas, a program manager with Chronicling America, a collection of historic American newspapers sponsored by the Library of Congress and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

“To my eye, these presentations reflect a remarkable moment as historical research pursued in real time, in a real, historically significant time,” said Reznick. “Each one demonstrates how and why history matters. It makes me wonder, perhaps, 100 years from now, that a great-grandchild of one of the students who presented today will look back on the project of her or his great-grandmother or great-grandfather to make sense of a pandemic they will be facing.”

Written by Andrew Adkins