Study Investigates Lack of Disclaimers on Facebook and Google’s Political Advertising

June 21, 2019

A cloak of mystery often shrouds the inner workings of technological giants, but sometimes clarity is in plain sight. A Virginia Tech research team recently uncovered conclusive details about the roles Facebook, Google, and the Federal Election Commission played in digital advertising around the U.S. presidential election of 2016.

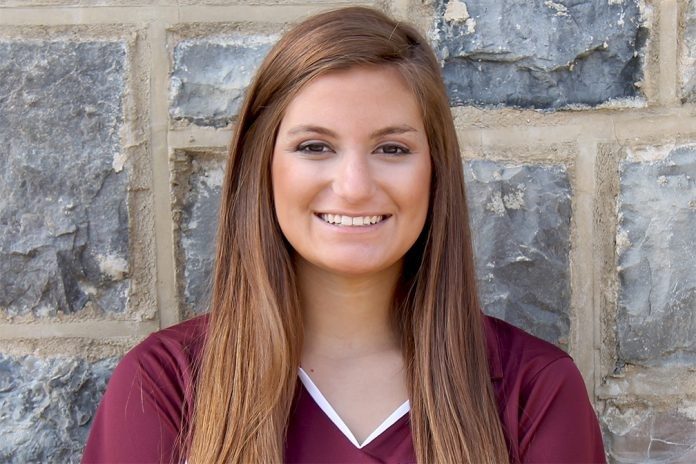

Katherine Haenschen, an assistant professor of communication in the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences, and Jordan Wolf, a 2018 graduate of Virginia Tech’s master’s program in communication, collaborated on the first academic research study to look specifically at how Facebook and Google deadlocked the Federal Election Commission’s efforts to regulate digital political advertising.

Haenschen and Wolf wanted to know what motivated Facebook and Google to seek disclaimer exemptions from the Federal Election Commission and why the independent regulatory agency failed to regulate digital advertisements leading up to the 2016 election. Their study — recently published by Telecommunications Policy, the International Journal of Digital Economy, Data Sciences and New Media — explored how the two platforms avoided disclosing who paid for advertisements related to the election.

The research team analyzed digitized versions of primary-source documents on the Federal Election Commission’s website to understand how Facebook, Google, and the commission perceived the need for online advertising disclaimers before the election. The authors searched through advisory opinions, which are official commission responses to questions about the application of federal campaign finance law to specific situations. The team identified three advisory opinions comprising 114 documents relevant to their study.

The analysis by Haenschen and Wolf uncovered persistent themes. The platforms showed, for example, both a desire to maximize profit and a leaning toward technological constraints as an excuse for noncompliance — or a lack of willingness to change advertisement sizes to accommodate disclaimers. The authors also noted two other themes: the potential for digital ads to deceive the public and the use of digital tools to win elections.

The researchers then investigated the documents from each of the advisory opinions to determine which themes dominated in terms of the platforms and the commission’s response to them. The team found that in 2010, the commission had its first opportunity to address disclaimers in digital advertising when Google requested an advisory opinion. Despite requirements developed in the 1970s that called for the reporting to the commission of paid political advertising expenditures for print, television, and radio, along with disclaimers on political advertisements identifying who paid for them, the commission allows for two exemptions.

“The first exception is a small-items exemption for items — such as lapel pins and bumper stickers — that don’t have room for a disclaimer,” Haenschen said. “The other is the impracticable exemption for media in which using a disclaimer makes little sense. This is basically limited to skywriting, water-tower signage, and apparel.”

Marc E. Elias, an election lawyer, represented Google in its request for a small-items exemption for text-only search ads. In addition, Elias wanted to know whether the advertisements linked to the sponsor’s website with the disclosure would be a sufficient alternative.

“A thematic analysis of documents from Facebook and Google reveal that both platforms were primarily motivated by profit to seek an exemption, basing their need on their business model of selling character- and size-limited ads, rather than any inherent technological limitations of the medium,” Haenschen and Wolf concluded in their paper. The authors noted that both platforms neglected to argue that the telecommunications industry does not regulate ad sizes in terms of character-based limits.

The outcome was that the Federal Election Commission voted to issue a narrow advisory opinion that confirmed that Google’s practice of including a link to a website containing a full disclaimer satisfied the commission’s requirements. However, a split along partisan lines began to surface. The three Republicans on the commission supported an impracticable exemption while two Democrats and an Independent found no technological justification. This advisory opinion left others with minimal guidance on how to comply with digital political advertising.

Following this, Facebook, through Elias, sought a small-items exemption and an impracticable exemption for its digital political ads. Following the Google experience, Facebook did not include any alternative means for the disclaimers. This only widened the partisan rift within the commission, which became deadlocked. Commission members issued no advisory and ultimately the advertisements became unregulated.

Haenschen and Wolf’s research led them to conclude that the digital platforms manipulated the Federal Election Commission’s system to make greater profits from political advertising.

Where, the researchers asked, does this leave the American public in 2019? In 2010, they noted, there appeared to be little interest when the commission announced notices of potential rulemaking on internet ad disclaimers. Only 14 comments were logged. In 2017, however, the commission received 149,772 comments to its updated public notices.

In a turnaround, the platforms are working on their own solutions. Facebook now requires a disclaimer on all ads with political content, verifies the identity and physical address of the payer, and claims to release all ads to the public in an archive. Google has put similar practices in place. But Google attorney Elias continues to lobby against requiring platforms to include disclaimers on digital political ads.

Written by Leslie King