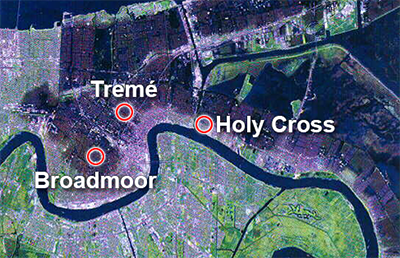

Post-Katrina New Orleans Case Studies from 3 Neighborhoods

This research examines the relationship between local knowledge and expertise in the rebuilding of three historic neighborhoods in New Orleans. Specifically, the project addresses the work of local groups and individuals as well as non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and other outside help-groups that targeted the repair and rebuilding of these communities after Hurricane Katrina. Also considered are the local, state and national government arenas as they impact the rebuilding efforts of citizens and NGOs.

The three neighborhoods of focus --Tremé, Holy Cross, and Broadmoor-- were carefully chosen to reflect a different set of: demographics, gentrification pressures, damage assessments, community organizations, and NGO participants. The findings of the project derive from the main focal lenses of observation and analysis that included environmental justice and participatory knowledge-making. By analyzing knowledge and practices from the ground up, the research provides rebuilding strategy analysis potentially relevant to other communities dealing with a disaster. Specifically, the nature of NGO connects and disconnects, and the dynamics of types of knowledge and their organizational uptake and distribution can inform future regulations, rules, procedures and policies relative to an urban environmental disaster. Mapping the transfer and translation of knowledge in rebuilding the historic part of the city and understanding flows and blockages of useful knowledge will inform other cities wrought by disaster or at risk for disaster in the future.

The Holy Cross neighborhood is a one square mile sub-district of the Lower 9th ward that fronts the Mississippi River on the higher ground of the natural levee of the Mississippi River. It dates back to the early 19th century and many of the houses were constructed using traditional Louisiana wood frame building styles in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1986 the neighborhood was made a National Register Historic District, the same year the Holy Cross Neighborhood Association was founded.

While neighborhood is not below sea level, when the canal walls broke the massive hydrostatic pressure of the water rushing in pushed a wall of water up onto the high ground. The water took less than a week to drain from these houses but because the main bridge into this cut-off part of the city was also the main bridge into the devastated part of the Lower 9th ward, all residents were not allowed entry into their flooded houses until many months after the storm. Additionally, Holy Cross and the Lower 9th ward were among the last neighborhoods to have utilities restored, delaying cleanup and rehabilitation.

According to the 2000 census report, the demographics of Holy Cross was 87% African American, 10% white and 1% Hispanic and after Katrina (2010 census) the population was 89% African American, 7% white, and 2% Hispanic. The housing unit vacancy rate was 15% before the storm and 41% after according to the above data source. This is compared to a city (parish) wide vacancy rate of 12% before and 25% after the flood in 2010.

This neighborhood was chosen as a case study because it represented an emergent, concept-driven dynamic of NGO-driven activity and citizen participation in a post-disaster context. The majority of the help groups and NGOs that came into Holy Cross were focused on environmentally sustainable rebuilding technologies and allied strategies. The neighborhood association embraced this approach and by 2012 over 75 “green” NGOs and outside groups had worked in the community. The idea was to transform Holy Cross into a leading example of a green, carbon neutral, low-income and working class community.

See the Publications and Anaysis & Comparison sections of this site for a more in-depth explanation of the research project and its findings.

The Broadmoor neighborhood occupies land that was once a lake at one of the lowest points in the central part of the city. Much of the housing dates from the 1920’s and is primarily raised basement bungalows and typical wood-frame shotgun-style houses. It was listed as a National Register Historic District in 2003.

The demographics of Broadmoor before Katrina, according to the 2000 census, reflected those of the city as a whole: 68% African American, 26% white and 4% Hispanic. Economically, however, it was somewhat poorer than the city as a whole with 32% of the households living in poverty. According to the 2010 census, after Katrina, Broadmoor was 61% African American, 29% white and 7% Hispanic also closely reflecting the post-disaster demographics of the city as a whole. The housing vacancy rate before the storm was 10% and afterwards (in 2010) it was 31%. . This is compared to a city (parish) wide vacancy rate of 12% before and 25% after the flood in 2010.

Unlike, Holy Cross (and somewhat Tremé), Broadmoor had vast economic disparities that tracked mostly along racial lines. Napoleon Avenue, a wide boulevard that divided the community, had expensive houses that sold for several hundred thousand dollars on the uptown side and on the downtown side were modest homes and many, sometimes blighted, rental properties.

After Katrina, 100% of the homes had sustained severe damage by high floodwaters that lingered for weeks. Ninety percent of the homes required major repair and remediation to be inhabitable again. The Broadmoor Improvement Association was the local neighborhood association prior to the flood and afterwards it became the citizen vehicle through which NGOs and residents worked in rebuilding their neighborhood.

Broadmoor was chosen as one of the three case study neighborhoods for this research because it represented lead advisory dynamic of democratic, participatory rebuilding. In this case, Harvard University’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs was the main organization assisting the neighborhood as it planned and rebuilt. This dynamic featured an NGO offering behind-the-scenes expertise and consulting resources that enabled a neighborhood to successfully self-determine their new direction for the future.

See the Publications and Anaysis & Comparison sections of this site for a more in-depth explanation of the research project and its findings.

The Holy Cross neighborhood is a one square mile sub-district of the Lower 9th ward that fronts the Mississippi River on the higher ground of the natural levee of the Mississippi River. It dates back to the early 19th century and many of the houses were constructed using traditional Louisiana wood frame building styles in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1986 the neighborhood was made a National Register Historic District, the same year the Holy Cross Neighborhood Association was founded.

While neighborhood is not below sea level, when the canal walls broke the massive hydrostatic pressure of the water rushing in pushed a wall of water up onto the high ground. The water took less than a week to drain from these houses but because the main bridge into this cut-off part of the city was also the main bridge into the devastated part of the Lower 9th ward, all residents were not allowed entry into their flooded houses until many months after the storm. Additionally, Holy Cross and the Lower 9th ward were among the last neighborhoods to have utilities restored, delaying cleanup and rehabilitation.

According to the 2000 census report, the demographics of Holy Cross was 87% African American, 10% white and 1% Hispanic and after Katrina (2010 census) the population was 89% African American, 7% white, and 2% Hispanic. The housing unit vacancy rate was 15% before the storm and 41% after according to the above data source. This is compared to a city (parish) wide vacancy rate of 12% before and 25% after the flood in 2010.

This neighborhood was chosen as a case study because it represented an emergent, concept-driven dynamic of NGO-driven activity and citizen participation in a post-disaster context. The majority of the help groups and NGOs that came into Holy Cross were focused on environmentally sustainable rebuilding technologies and allied strategies. The neighborhood association embraced this approach and by 2012 over 75 “green” NGOs and outside groups had worked in the community. The idea was to transform Holy Cross into a leading example of a green, carbon neutral, low-income and working class community.

See the Publications and Anaysis & Comparison sections of this site for a more in-depth explanation of the research project and its findings.