Reading the past

November 22, 2022

By Rachelle Kuehl

This blog article was originally published by the Center for Rural Education at Virginia Tech.

November 21, 2022

In October, my family and I drove from Virginia to Minnesota to say goodbye to my wonderful father-in-law, who passed away at the age of 84 after a long illness. My children missed a full week of school, and when we returned, I worked with my fourth grader, Jamie, to make up his language arts assignments. Together, we read several chapters of Blood on the River: James Town, 1607 by Elisa Carbone (2007), the historical novel his class had been reading during small-group instruction Blood on the River is a story about the first British settlement in America at Jamestown and serves as a perfect tie-in to the fourth-grade Virginia Standards of Learning for history and social sciences.

Although I have lived in Virginia for many years, I previously only had a vague sense of what went on at the Jamestown settlement, and reading this story with Jamie was a reminder of just how powerful a vehicle historical fiction is for teaching about events from the past. From this book, I learned about the Virginia Company of London stockholders who funded the expedition to America with the hopes of expanding the British empire and increasing their own wealth. I learned about John Smith, the commoner-turned-sea captain who (from the eyes of the narrator, Samuel), was a good leader because he stood up to corruption, worked hard alongside his hired laborers, and aimed to negotiate fairly and peaceably with the Powhatan people who had inhabited Virginia’s land long before the arrival of the British. Although I had already known that many settlers did not survive the first winter at Jamestown, I was able to experience the danger and loss of life on a personal level as Samuel described the constant quest for food and warmth and the persistent need to dig graves for those who died. I saw the way the Powhatan people were rightfully wary of the newcomers at first, but valued their humanity—and the opportunity to trade—enough to share nourishment and shelter, without which none of the Jamestown settlers would have survived. I met Pochahontas, who was a younger girl when she encountered the settlers than the Disney movie would have us believe. I learned how British people continued to arrive at Jamestown because letters describing the horrific conditions there were blocked by investors whose financial interests would have been threatened by their receipt. I learned that unscrupulous new leaders quickly unraveled the delicate trust built between Chief Powhatan and Captain Smith by plundering the Powhatan camps and forcing the chief and his people into a ceremony declaring them as British subjects.

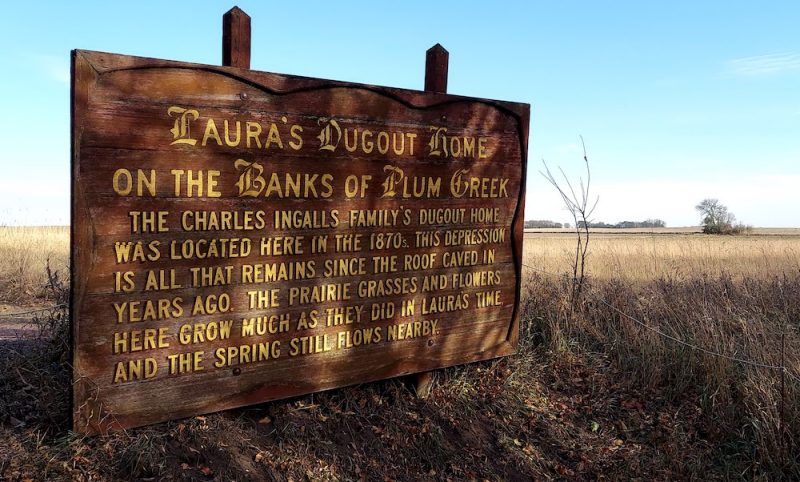

My father-in-law grew up in rural Walnut Grove, Minnesota, one of the places Laura Ingalls Wilder had lived and where the Little House on the Prairie television series was set. While we were nearby for his funeral last month, we visited some of the historical sites related to Laura’s life, including a museum gift shop that sold copies of the beloved books I grew up reading that taught me a very one-sided version of pioneer life. From Laura’s point of view (which was then shared by me as one of her many young readers), it seemed reasonable for White families to move westward, claiming land inhabited by others—sometimes forcibly—and to begin building farms and towns upon it. A novel I recommend to explore events in this region during this time period from a more nuanced perspective is Resisting Removal: The Sandy Lake Tragedy of 1850 by Colin Mustful, a Minnesota historian (and my brother!) who is also the founder of History Through Fiction, an independent press dedicated to sharing stories that combine historical research with compelling fictional narratives. Although I grew up in Minnesota and had read the Little House books dozens of times, I never knew about the forced removal of Ojibwe citizens by the US government Resisting Removal describes—nor had I ever heard of the massacre of 38 Dakota men ordered by Abraham Lincoln in 1862—until Colin started researching both events.

While we were in Walnut Grove, Jamie’s class was on a field trip to Jamestown. We hated that he had to miss it, so we’re planning to visit the historic site as a family this spring. Having read Blood on the River, I know I will take much more interest in seeing the places mentioned in the book and learning about the historical figures depicted as part of the story, and I’m sure Jamie will too.

Our reading of this novel was timely as we approach Thanksgiving this week, a time when, as a nation, we celebrate a story about the Pilgrims and “Indians” that is part of our shared cultural history but is based on a narrative that overlooks the atrocities inflicted on the Indigenous people who inhabited this land long before the Europeans arrived. To help our students—and ourselves—understand the truth of history, we can recognize Native American Heritage Month in our classrooms; we can read historical novels like the ones I’ve mentioned; we can pair historical novels with contemporary fiction to demonstrate the through lines connecting past and present events (Kuehl, 2022); and we can seek out other resources to help students avoid “The Danger of a Single Story” (Adichie, 2009). For nonfiction reading, I recommend An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz (2015), which was adapted for young people by Debbie Reese and Jean Mendoza (2019). The National Congress of American Indians has resources available on their website, and Virginia Tech’s American Indian and Indigenous Community Center has programs and resources designed to educate the public and to celebrate the contributions of Indigenous people historically and in the present day.

At the beginning of each chapter of Blood on the River, Carbone embeds quotations from primary source documents to show where she obtained the information to construct her story. Many of the quotations are from John Smith’s own writing about the events in Jamestown, which he wrote from England after he suffered an injury and left America to recover. Was he actually a “good guy,” then, or did he merely wield his pen, a weapon his character describes as “much more powerful than [the] sword” (Carbone, 2007, p. 88), to paint himself in a flattering light? As educators, it’s crucially important to help students think critically about the answer to that question when approaching any historical text. Who is telling the story? What is their goal in writing it? Whose perspective is left out? As we gather with family and friends for the holiday, let us be more aware of the stories we’ve been told and of our duty as engaged citizens to examine and, when necessary, disrupt them.

Rachelle Kuehl is a research scientist in the Center for Rural Education at Virginia Tech and the project manager for the Appalachian Rural Talent Initiative. Her articles about children’s literature and literacy education have appeared in journals such as The Reading Teacher, The Journal of Children’s Literature, English Journal, English in Education, and Reading Horizons.

To subscribe to the Center for Rural Education at Virginia Tech's blog, click here.