Virginia Tech history class connects 1918 flu outbreak to COVID-19 pandemic

April 6, 2020

As communities across the globe confront the COVID-19 pandemic, a group of Virginia Tech students is exploring the history of another major outbreak.

The 1918 influenza epidemic has served as the central research project for Professor of History Thomas Ewing’s Topics in the History of Data in Social Context course.

When Ewing, an expert on the history of epidemics, selected the research project last fall, he didn’t anticipate the themes of the course would dominate daily life in the spring.

After the March transition to online learning, students in Ewing’s history class have continued to pore over news articles and other data related to the 1918 outbreak. The class is now preparing to collaborate with the National Library of Medicine on a virtual symposium based on the students’ research.

The program, “Reporting, Recording, and Remembering the 1918 Influenza Epidemic,” scheduled for April 29 from 2 to 4 p.m., is made possible through the National Library of Medicine’s formal partnership with the National Endowment for the Humanities to collaborate on research, education, and career initiatives. This partnership has also resulted in a summer seminar for K–12 teachers on the 1918 flu pandemic and a workshop and book on viral networks.

The class is focusing on three main themes that directly connect the historical lessons of 1918 to the current challenges of COVID-19: how newspapers reported on the epidemic during the most severe weeks; the effect of social distancing policies implemented in cities and states; and how communities recovered from the worst effects of the epidemic.

During a recent online class discussion, students detailed what they’ve learned so far, and how that knowledge has helped them understand the gravity of COVID-19.

“I think I took COVID-19 a lot more seriously than many of my peers when the first cases were reported in America,” said Louisa Glazunova, a junior majoring in communication science and social inquiry. “We’ve been studying how quickly the flu peaked in 1918 along with the numbers from back then. Seeing the rise in cases in 2020 has been eye opening.”

Each student is studying news reports from individual communities in addition to broader statistics from 1918.

Alessia Scotto di Luzio, a sophomore majoring in electrical engineering, compared and contrasted news coverage from 1918 to current day. Citizens had no social media, Scotto di Luzio noted, but most newspapers did provide daily updates. Total numbers were not featured as prominently in some newspapers.

“Today, we can just go online and look up ‘coronavirus’ and see direct numbers,” said Scotto di Luzio. “I think this made it kind of hard for people back then to understand the extent of the flu.”

Similar to today’s messaging, health officials and state governments encouraged citizens to practice social distancing and take other precautionary measures, the students said. Governments closed schools, churches, and other venues to prevent large gatherings.

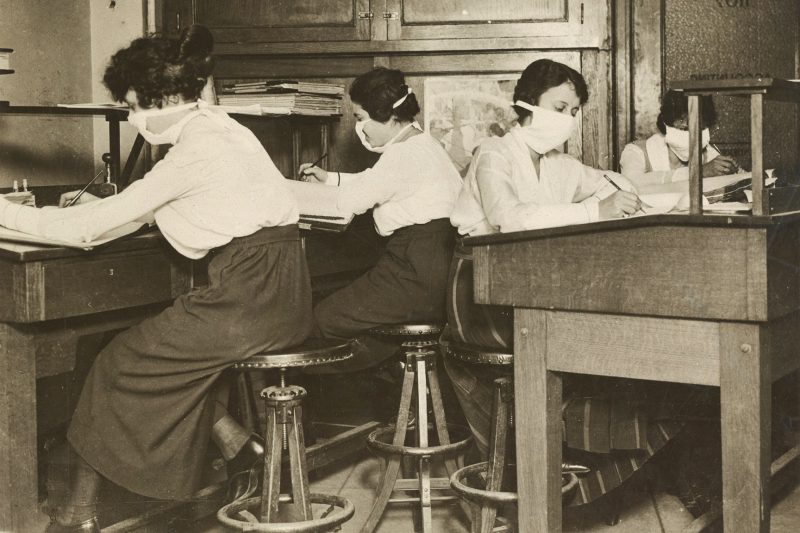

Many cities encouraged residents to wear personal protective equipment. Fiona Tran, a junior majoring in computational modeling and data analytics, found an article from Ogden, Utah, that mentioned residents rushing to purchase face masks. Some cities, including San Francisco and Seattle, forced residents to wear masks by law.

Students have found some instances of rule breaking, as well as refusals to take precautions. Freshman university studies major Matt Mirabella found a news article about a mayor who was penalized for refusing to close bars. Katie Kromer, a sophomore modeling and data analytics major, learned that some San Francisco residents served jail time for not wearing protective gear.

The 1918 outbreak provides important lessons about taking appropriate public health measures, relying on expert guidance on the potential impact of a disease outbreak, and understanding the uncertainty of predicting the scope and severity of an epidemic, said Ewing.

“In 1918, public health officials warned of the potential impact of a widespread disease outbreak, yet they also underestimated how many people would fall ill and the total number of deaths,” said Ewing. “In 2020, Americans received similarly inconsistent messages, as the warnings of public health experts about the need for urgent and strict measures were undercut by other officials proclaiming that the threat was exaggerated and the measures were not needed.”

In contrast to 1918, however, the voices of those urging alarm in 2020 were heeded more quickly, leading to officials implementing measures on a wider and more complete scale, Ewing noted.

Officials are using statistics from the 1918 epidemic to guide public policy recommendations in 2020, said Ewing.

“The predictions about the number of cases and deaths, the potential for flattening the curve, and the extent of the epidemic all use data from the 1918 pandemic to inform today’s computational analyses,” Ewing said.

For more information about Virginia Tech’s response to COVID-19, along with resources for the community, see the Virginia Tech COVID-19 (Novel Coronavirus) Overview page. To learn more about the April 29 videocast, read “Virginia Tech history students to present research findings on the 1918 flu pandemic during live National Library of Medicine videocast.”

Written by Andrew Adkins