Digital Archive Helps Interpret the Fourth of July in the Civil War Era

June 27, 2017

For many Americans celebrating the Fourth of July holiday translates to engaging in lighthearted festivities: firing up the grill for a day of barbecuing and revelry, and at dusk settling down to enjoy the twinkling of fireworks in myriad colors against a dark evening sky with neighbors, friends, and family.

During the Civil War era, however, celebrating the holiday was at times anything but civil, and Independence Day was not thought of only as a day to relax and picnic. The Fourth of July was a day steeped in serious political discussions about the existential nature of being American. Discussions would sometimes even turn violent, and often they were racially charged.

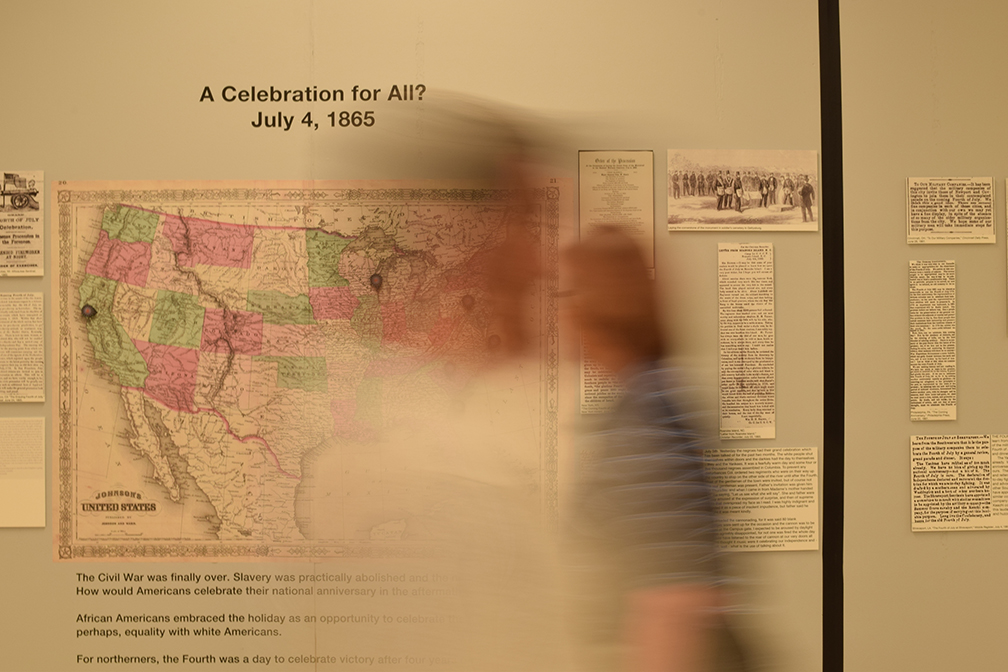

In order to get a better idea of how the holiday was celebrated in the past, Virginia Tech researchers have created an interactive digital archive called Mapping the Fourth of July: Exploring Independence Day in the Civil War Era. The archive gives 21st century Americans a glimpse of what revelers experienced in the period leading up to the Civil War, during wartime, and into Reconstruction (1848-1877).

“The big difference for me between now and the Civil War era is that Americans no longer really use July 4th in the way they used to back then — as a forum to argue about what America meant and who counted as a true American,” said Paul Quigley, the James I. Robertson Jr. Associate Professor of Civil War Studies in the Department of History and director of Mapping the Fourth of July. “Working on the website has really driven home the stakes of Independence Day for race relations and political rights after the war.”

Quigley, who is also the director of the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies, developed the crowdsourced project with colleagues David Hicks, co-director and professor in the School of Education, and Kurt Luther, co-director and assistant professor in the Department of Computer Science. The project is funded by grants from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission and the Institute for Creativity, Arts, and Technology.

Luther, who is also associated with the Center for Human-Computer Interaction, led the development of the interactive components of the site using crowdsourcing, a research approach where any member of the public can contribute to the archive. Crowdsourcing allowed the project to take on a life of its own and for researchers and the public alike to dig deeper into primary source documents.

“Crowdsourcing is a powerful way to get the public involved in a historical project,” said Luther. “Our project asks the crowd to go beyond simple transcription and think about the meaning and context of these documents. This project allows transcribers to not just learn about the history of the Civil War, but to contribute authentically to new historical research by analyzing the digitized primary documents that cover a wide range of human experiences.”

Originally, around 4,000 documents were loaded into the database of the site, hundreds of distinct documents have been transcribed, and so far 3,005 users have guest accounts.

“Using computer science to understand national identity is really a no-brainer,” said Luther. “Software like ours help historians cast a wider net in their research, to dig deeper, and even to ask and answer new types of historical questions. For Mapping the Fourth of July, the data is telling us about how people in the past lived through the Civil War era through documents, many of which relay extremely emotional and racially charged feelings of the time. In that way, technology also helps enormously with illuminating human behavior and shedding light on the past.”

Written by Amy Loeffler