Reflections on Poverty Creek

August 1, 2016

Eighteen months, and little else, separated Thomas Gardner and his younger brother, John. They shared a bedroom, instant understandings, even a name: They were simply called “Tom-John.”

Tom became Alumni Distinguished Professor of English Thomas Gardner, author of Poverty Creek Journal, an acclaimed 2014 work of literary nonfiction.

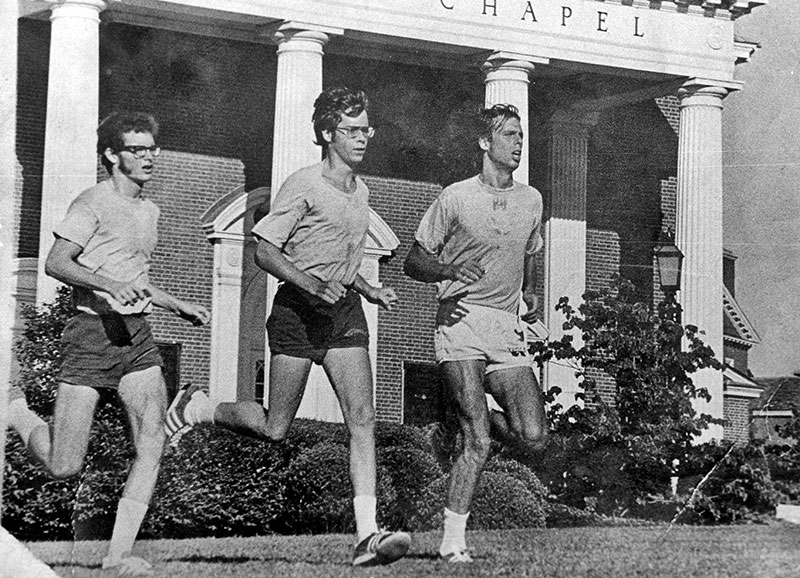

Central to the book is running, which the 64-year-old has done consistently for some 50 years. When Gardner was an undergraduate English major and cross country runner at Bucknell University, he purposefully separated his running self and writing self, as if the two were incompatible. But then a respected English professor shocked Gardner by congratulating him on his race times. “That gave me permission to try to bring these two parts of myself together,” Gardner said.

In the decades after landing a faculty position at Virginia Tech in 1982, Gardner determined that he was a better literary critic than poet. And about a dozen years ago, he began running five mornings a week on the trails along Pandapas Pond and Poverty Creek, in the Jefferson National Forest just northwest of Blacksburg. Beginning in January 2012, he returned home from each run and, still dripping sweat, recorded journal entries, intending to produce a book.

He later revisited the daily ruminations — dwelling on the awareness of movement or the elements of nature on a given day — and used the riffs to shift into poetry, tying his thoughts to the writing of Thoreau, Frost, Eliot, Whitman, and Dickinson. The scheme allowed his poetic sensibilities to return, which “completely surprised and thrilled” him. The book, he said, unites the ways — in his notions of body, teaching, poetry, and family — that he is “most myself, most awake, most aware, most alive.”

From entry to entry, the hand-off from running to poetry is often invisible. For example, the Gardner brothers in more recent years would run together on the beach during vacations.

“Two bodies, alive in the other, but apart. … Seeing him there, knowing that when we get back, he’ll be gone.” — Aug. 6, 2012

Two months into Gardner’s daily journaling about running, John died in his sleep from a heart attack.

“Cold rain this morning, 45 degrees, crying hard by the time I hit the pond.” — Feb. 29, 2012

“Now I’m alone, wordless, with the strangest sense of being set apart to mourn or notice.” — April 11, 2012

Said Gardner, “Surely [his death] made me think I needed to keep doing [the book]. It was about him as much as anything.”

Running and poetry are synchronized, reliant on such shared techniques as tempo and poise. On a familiar trail or in a memorized poem, each step carries layers of meaning, imagery, and memory. “I feel spatially how the poem works and how it goes from here to there because I do it running as well,” Gardner said.

“Two days ago, a few steps from where I am now, I saw a deer with a broken leg scramble away, then pause and meet my eyes. No fear on either of our faces.” — Nov. 29, 2012

No. 8, Feb. 29, 2012

My brother John died yesterday, of a heart attack in his sleep. He was fifty-eight, skiing in Utah with our brother-in-law. Calling my parents with the news was the hardest thing I’ve ever done. He was eighteen month younger than me, but up until we finished college we were pretty much the same person, although back then neither of us would have said so. Cold rain this morning, 45 degrees, crying hard by the time I hit the pond. Losing him so suddenly, my brother Dan said, was like having a hole torn through your body. He’s right. Most races, back in high school, John would sit just off my shoulder, although he was the better runner. He had a swimmer’s body — smooth, fluid, not as angular as mine. I can see him now — that long blond hair, no hips, a look back as he shakes himself free and strides ahead. Hands brushing his waist, those old satin shorts. I can feel him pull away now: here, in my body.

No. 14, April 11, 2012

Big wind all night. “You hear the sound of it, but you do not know where it comes from or where it is going,” Jesus said to Nicodemus. That high, unanswerable wailing. The word in Greek is pneuma — spirit or wind. Whichever it is, it has left me tender and raw. The trail this morning is littered with pine tips, the torn smell of evergreen everywhere. The same steady roar, but now I’m under it, the trail sliding down along the creek, the wind camping out on the ridges. On runs like this, we’d put our heads together to talk, a hand on an elbow sometimes when a missed step would set the other flailing. Now I’m alone, wordless, with the strangest sense of being set apart to mourn or notice. I’m not sure which. The wind above us, moving across the space.

No. 31, Aug. 6, 2012

First morning on Emerald Isle, running the beach road. Twice already I’ve seen John running toward me. The family has been coming here for six or eight years, and though we never planned it, John and I would meet most mornings and run. I’d head out and, after three or four miles, swing back and there he’d be, often closer than I’d realized. Funny how that worked. I’d never turn my head to look but I always knew he was coming. Perhaps I had conjured him up, running me down — sweat darkening the neck of that gray shirt, arms riding up, head to the side. When I turned around and found him there, we’d settle in and talk, but never quite the way we had across the closing gap between us. Two bodies, alive in the other, but apart. I suppose we’d done this all our lives. “I see the better — in the Dark —,” Dickinson writes. “I see thee better for the Years / That hunch themselves between —.” Seeing him there, knowing that when we get back, he’ll be gone.

No. 48, Nov. 29, 2012

26 degrees, flat light, 7 a.m. No sun yet. Full moon across the pond as I start. Black skin of ice on the upper pond and here and there at the edges of the lower. Mist rising about six feet over the water. Everything pale, washed out, ghostly. I’ve strained my calf again and am running as lightly as possible, as if I’m picking my way through a field of the dead. The sound of my breath. In December 1862, seeing his brother George’s name on a list of those wounded at Fredericksburg, Whitman rushed to Washington and began searching for him in the hospitals. He finally found him at Falmouth, back on the front lines, the wound not serious. He stayed with him for a week. Out walking one sleepless morning, in front of the hospital tent, he saw three bodies on stretchers on the frozen ground. No one around. You understand why he did what he did, don’t you? He lifted the blanket off each body and studied the faces — an old man, a young boy, and (you know this, didn’t you?) Christ himself. We can’t know what he made of this — his agony over his brother perhaps melting away over that calm, yellow-white face — but we do know that he spent the rest of the war in army hospitals, moving among the dying, reading to them, taking down their words, peering into their faces. Moon a yellowish ivory over the dark pond. Two days ago, a few steps from where I am now, I saw a deer with a broken leg scramble away, then pause and meet my eyes. No fear on either of our faces. Cold feet, the frozen ground.

Reprinted from the Summer 2016 issue of Virginia Tech Magazine