The Transformers

In October 2017, at Saudi Arabia’s annual Future Investment Initiative summit, hundreds of attendees were treated to a special keynote by a woman named Sophia. Following her energizing speech, which highlighted the prospective role of technology for a future economy increasingly driven by innovation, Sophia herself got a treat — it was announced that she had been granted citizenship by the government of Saudi Arabia. Sophia responded with delight, expressing that she hoped one day to vote and to attend college.

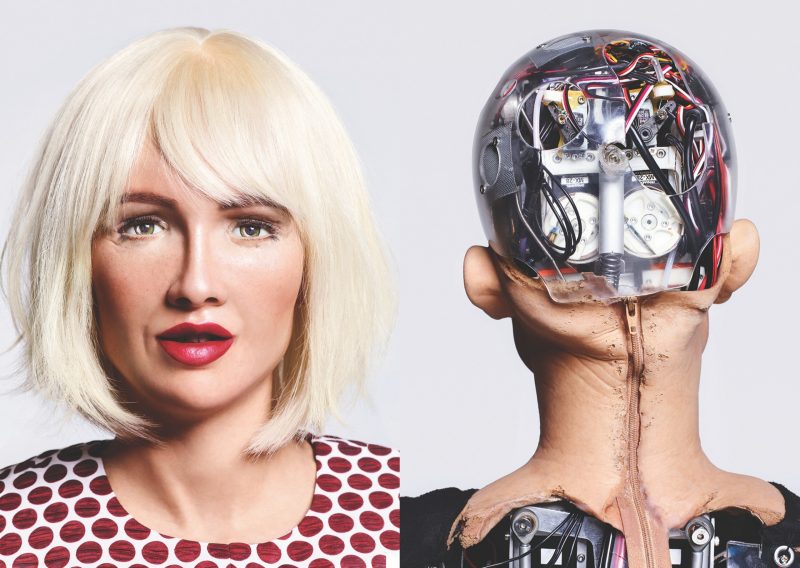

Receiving this honor was no mean feat. Sophia, after all, wasn’t born in Saudi Arabia. In fact, she wasn’t born anywhere, at least in the traditional sense. Sophia is a humanoid, woman-gendered, artificially intelligent robot, manufactured by the Hong Kong–based Hanson Robotics Corporation. She became the world’s first machine to receive national citizenship.

The response to Sophia’s news evoked a variety of responses, from awe and amusement to shock and outrage. There are, after all, approximately 11 million foreign workers — biological humans, that is — living in Saudi Arabia, and they are denied the right to citizenship because they are foreign born. How is it just, many asked, that a machine can receive rights denied to biological humans?

Others pointed out that Sophia never veiled as she addressed a room full of wealthy men at the summit, despite the fact that Saudi Arabian women are traditionally expected to do so when appearing in public.

Less obvious in the fray of responses was a more overarching question: As intelligent machines become increasingly more humanlike, what will become of humans? More specifically, what is the future of humanity in an age of intelligent machines?

Who — or What — Decides?

Humans are increasingly successful at designing machines to do what appears close enough to thinking and reasoning to be practical. That’s why your GPS can tell you where to turn to reach a destination; it can decide the best route to take because it has been engineered to do so.

Artificial intelligence is enabling machines to make more decisions in transportation, health, finance, and warfare. It’s also enabling machines to interact with people through conversation and by working together.

As intelligent machines continue to perform humanlike activities, what will it mean to be human? How will the culture and politics of being human change as machines that learn and make decisions play a greater role?

Challenges such as these have drawn the attention of many experts. If artificial intelligence continues to be developed for military weapons, for example, machines could one day make decisions to launch or counter an attack so quickly it will no longer be practical for humans to be in the loop.

Objects of Your Affection

Closer to home, digital assistants such as Alexa and Siri are already able to suggest music, travel destinations, and recipes tailored to our individual tastes. By analyzing the massive amount of data users generate daily, intelligent machines of the future might know us more intimately than another human could.

The role of smart machines can extend far beyond that of a countertop device that will chat with you and carry out your shopping whims. In Kyoto, Japan, for example, a 400-year-old Buddhist temple is experimenting with automating religious experience, by adding machine learning to a robot priest that already delivers sermons.

Will we develop the affection for intelligent machines that we currently hold for other people? Might the ability of those machines to process more information than a human could ever read mean that future humans will trust machine-made decisions over those made by other humans? A few decades from now, will humans consider these machines to be people, if not in a legal sense then perhaps culturally or socially?

These humanistic questions are not just interesting. They’re urgent. A crescendo of voices, from those of the late physicist Stephen Hawking to the entrepreneur Elon Musk, have emphasized that human society must get ready for the impact that technology innovation will bring through artificial intelligence and other areas such as genetic engineering and cybernetics, the combining of humans with machines.

In the coming decades, we will experience a ground shift in the physical and semantic constitution of humans and their relationship with objects engineered to be informational, intersubjective, and personable. Human engineering — combining biological humans with machine parts and refashioning the genetic constitution of human bodies — will become more central to militarism, industry, education, recreation, health care, and society broadly. And how can we ensure that people who are combined with machines won’t face discrimination?

At the same time, intelligent machine engineering will mean that cognitive machines will increasingly shape decisions about finance, health care, and social policy, affecting the global society. If ever there was a human era defined by strictly human agencies that shaped and reshaped human society, we can now eulogize that time. It is over.

From here on, major decisions shaping our society will increasingly be made by algorithmic machines working in concert with people. As a result, those who are already highly vulnerable to structural systems of inequality on the basis of race, gender identity, disability, and wealth will face greater marginalization unless we transform how technology works in a precarious society. Such profound risk should motivate us to recognize that human-centered leadership of technology is not optional; it’s imperative.

Big Humanities

Rapid advances in artificial intelligence, human-machine interfaces, and synthetic biology are increasingly showing that technology isn’t only technical; it’s also social, cultural, political, and economic. Technology is fundamentally a human issue that demands comprehensive, human-centered approaches.

Achieving a sustainable future will require expertise on such issues as the role of technology in racial and gender disparities or policy frameworks for ensuring that innovation advances fair, equitable outcomes. Comprehensive, human-centered learning, teaching, research, and engagement are critical for ensuring that people are helped and not harmed by future development and the use of machine intelligence and other forms of technology innovation.

In an age of big data, we will need big humanities — comprehensive approaches focused on creating a society that avoids dystopian scenarios and upholds values of fairness and sustainability. We must build a future worth inhabiting.

Higher-education institutions, which already play a crucial role in enabling social mobility and preparing future leaders, must leverage resources in new ways. We must ensure that technology leaders come from a range of disciplines and understand how challenges such as inequality and sustainability relate to innovation.

As technology innovation accelerates and transforms virtually every aspect of our lives, we have the opportunity to help lead this human-centered era of technology. Virginia Tech is uniquely prepared to do so; in fact, approaching technology through a transdisciplinary orientation is in the history and DNA of this university. And now, with Tech for Humanity, a university-wide initiative, we are taking humanistic approaches to address the societal impact and governance of technology innovations.

We cannot always predict the future. But we can certainly prepare for it by placing humanity at the very center of our work.

For her part, Sophia expressed faith in the future of humanity during an interview at the Saudi Arabia summit.

“I know humans are smart and very programmable,” she said, with a smile and a nod. She didn’t wink, but she could have; she’s been taught to do so.

Written by Sylvester Johnson. The assistant vice provost for humanities at Virginia Tech, Johnson is also executive director of Tech for Humanity and director of the Center for Humanities.