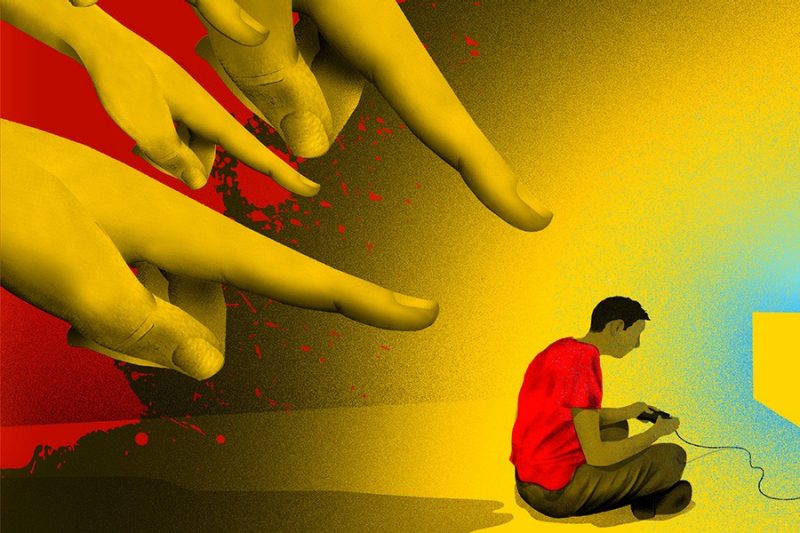

The Blame Game

Researchers have found no definitive evidence linking video games to violent crime. So why are people still talking about a correlation?

One hundred players parachute into a remote island and sprint toward hideaways scattered across the forested land.

Confrontation is imminent.

Simulated weapons drawn, gamers practice survival techniques in an intense “battle royale.” Only one will emerge victorious.

The game is Fortnite. Since 2017, it’s emerged as the most popular title in the video game industry, with its developer reporting a peak of 250 million users worldwide.

Fortnite attracts young and older gamers alike and follows a simple concept: Choose a character and weaponry, then build strongholds to defend against opponents.

Like most of Fortnite’s counterparts in the booming video game industry, violence is its core theme. According to the American Psychological Association, 85 percent of video games on the market contain some form of violence.

The use of violent content in video gaming isn’t a new phenomenon. Developers have featured it in their products for decades. Simultaneously, the debate surrounding violence in games has persisted, with some public figures linking video games as a factor in mass casualty incidents and other criminal activities.

In response, scholars such as James Ivory, a professor in the Virginia Tech Department of Communication, point to the science.

“It’s certainly okay to be morally opposed to putting kids in front of gore in video games, but that’s not the same thing as scientific harm,” says Ivory. “There’s virtually nothing in the way of evidence that violent video games affect behaviors like serious violent crime.”

For more than a decade, Ivory has researched the social and psychological dimensions of new media and communication technologies, including the content and effects of video games. The New York Times, CBS News, and other major news outlets have cited Ivory’s expertise in articles on the subjects.

Ivory is also director of the Virginia Tech GAMER Lab, a small facility dedicated to investigating the social impact of video games, along with virtual and simulated technologies. GAMER is short for Gaming and Media Effects Research.

Undergraduate and graduate students have participated in studies since 2006. Over time, Ivory says, the lab drifted from researching possible links between violent video games and aggressive behavior after he and other scholars found limited evidence for societal effects of media violence.

When it comes to abstract forms of aggression, researchers tend to have mixed opinions about whether video games play a role. But on the topic of serious violent crime, Ivory says, research has consistently indicated the effects of violent video games are negligible.

A 2004 report by the U.S. Secret Service and U.S.

Department of Education found only 12 percent of perpetrators in mass shootings had interest in violent video games. As of 2019, the Secret Service has never identified video games among useful factors in perpetrator profiling.

The American Psychological Association’s Society for Media Psychology and Technology division released a statement in 2017 asking media outlets and politicians to avoid linking violent video games to mass shootings.

“It’s like saying the perpetrators wear shoes,” Ivory says. “They do, but so do their peers in the general population.”

Continuing to mention video games as a possible factor in serious violent crime distracts from research into crime prevention methods based on known causes, according to Ivory. He points to other socioeconomic factors proven to significantly affect the likelihood of violent crime, such as substance use, physical abuse, and poverty.

So why do video games still receive a large share of blame?

“To me, that’s the interesting question,” Ivory says. “When you hear people talk about video games after a violent incident, it’s useful to ask yourself two questions. What does this person not want to talk about? And what about this crime is making people want to look to video games as a culprit?”

Political and commercial motivations are possible reasons, Ivory says. Public figures, including President Donald Trump, have recently criticized video game content following mass shootings. And the National Rifle Association has joined other pro-gun ownership organizations in blaming the video game industry in the wake of tragedies.

Another possible reason for the rhetoric involves racial bias, Ivory says.

In 2019, the GAMER Lab conducted a study that tasked subjects with reading mock news stories about violent crimes. In each article, the perpetrator, an 18-year-old video game enthusiast, was described as either black or white. The study found participants were more comfortable with the idea that video games played a role when the suspect was white.

Through the lab, Ivory also worked with academics at three other universities to produce a study on racial stereotypes and school shootings. After analyzing more than 200,000 news stories of 204 mass shootings committed in the United States, Ivory and his collaborators found coverage was eight times more likely to mention video games when the shooter was white than when the shooter was African American.

“The idea that we talk about certain perpetrators differently in terms of violent video games is problematic,” Ivory says, “because it might suggest we look for excuses for some perpetrators more than for others.”

For Ivory, the continuous search for a link between video games and violent crime also means ignoring problematic topics within the video game industry itself.

“We know video games are a big part of many people’s lives,” he says. “We also know that they don’t cause mass shootings. But we don’t know much else about the role they play in society.”

Beyond advancements in visual technology, video games have evolved from a solitary media activity to a growing social and communal activity online. Livestreaming services such as YouTube and Twitch attract millions of viewers. And the growth of esports has turned a hobby into a profession or even a college scholarship.

In online gaming, players often chat through headset microphones or keystrokes. The communication systems are meant for positive interaction, and to help teams strategize. Players can connect with real-life friends or make new ones through in-game chats.

Sometimes, though, the conversations can turn toxic, creating a hostile environment. Ivory has dedicated a large part of his research to the social aspect of online communication in video games. The GAMER Lab studies the frequency of racial slurs within game chats, for example.

Gender-role stereotypes in gaming discourse is another issue that has drawn the lab’s attention. In a field experiment involving the first-person shooter game Call of Duty, another major title in the industry, the lab’s research found that a female player gained more friend requests from other users if she was quiet or nice. A male player made more friends if he was talkative or even somewhat rude.

Ivory has also studied how gender-role stereotypes continue to influence the characters created by game developers.

“The evidence suggests that even if you’re in a video game pretending to be a World War II soldier,” he says, “you can’t escape stereotypes in gender roles.”

Game makers have taken some steps to address misogyny and other toxic behaviors in their chat windows. Most popular titles allow users to mute or block players, and to report abuse. In some cases, players can receive a suspension or expulsion for poor behavior. Still, some parent groups and other organizations have raised concern about harassment in online games.

Because of the rapid pace of the industry’s growth, research into these issues has been slow to catch up. The fixation on studying whether video games influence violent crime certainly hasn’t helped, Ivory adds.

“I suspect video game companies are happy that much of the focus has been on violence, when we could be talking about other important issues,” says Ivory. “We’re not finding these video games are turning people into hardened criminals. But we’re uncovering other important issues we need to talk about, like the way we interact with each other in video games, the way we think about gender roles, and the way games portray people.”

Written by Andrew Adkins and illustrated by Brian Stauffer