Future-Proofing the Future

These are not your mother’s automatons. From the corner of your eye, you see it. All steel and moving parts, the robot stands in the shadows. It senses your heart rate, and with its unhuman and mechanical movements, the machine edges imperceptibly closer to you. One last thought lingers in your mind. What will it be like when these automatons and their evil corporate puppet masters enslave humanity? Suddenly you feel sharp jolts from the implanted microchip in the soft underside of your wrist.

You awaken.

Your smartwatch, which has been tracking your sleep, is gently buzzing. It tells you that now is the optimal moment to rise and face a new day. A soft, artificial yet pleasant voice welcomes you into consciousness with a morning greeting, a weather update, and a quote that, based on your recent browser search history, will inspire you. You inhale the scent of freshly brewed coffee as your smart mattress signals to your coffee maker that your sleep cycle is now over. The future of your nightmares seems less possible.

But is it? In this modern age, technology’s future can seem dark and apocalyptic or fantasy-like, with self-flying cars that allow you to snag an extra hour of sleep during your morning commute. Tomorrow sits on a precipice between the potential possibilities.

Rather than waiting to see how the future evolves, Virginia Tech is focused on promoting a future in which emerging technologies are in service to humanity. The university is taking human-centered approaches to address the societal impact of technological innovation.

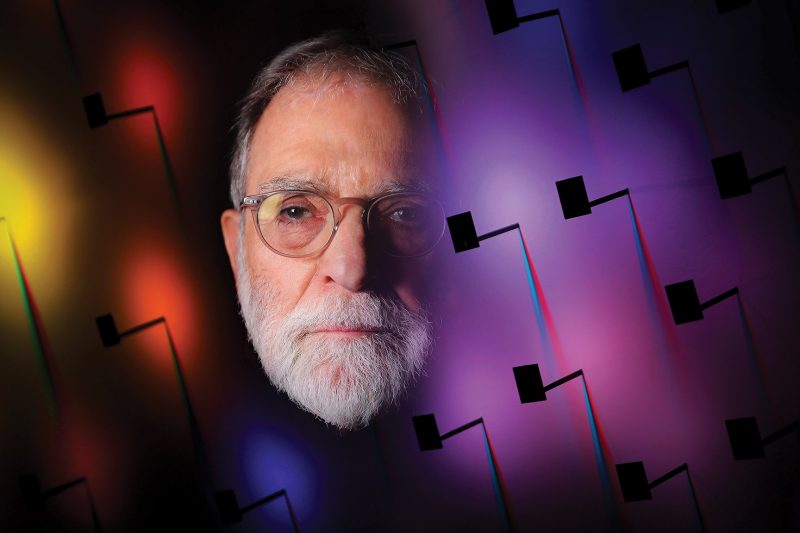

“We need multiple strategies,” says Sylvester Johnson, assistant vice provost for the humanities. “Virginia Tech is uniquely positioned to lead in this new era. Regionally, nationally, and globally, we are setting a new standard with Tech for Humanity, a university-wide initiative focused on the human-centered guidance of technology.”

Under Johnson’s leadership, Tech for Humanity focuses on ensuring a thriving future for humanity and emphasizing ethics, empathy, policy, equity, creativity, inclusion, diversity, and sustainability. Through the Center for Humanities, which Johnson also directs, collaborations enhance the university’s efforts to create responsible technologists.

“These are people who care, commit to, or are involved with advancing human interests through technology,” Johnson says. “And they try to achieve outcomes that serve all of humanity.”

Tech for Humanity scholars and the Center for Humanities encourage research among faculty and students in arts, human-centered social sciences, humanities, and technological fields. They work within their disciplines and collaborate with faculty across Virginia Tech. The center also partners with the university’s legislative liaisons and faculty members in the Department of Political Science and the Policy Strategic Growth Area to engage legislators in issues of public policy. It additionally educates corporate entities on matters of ethics and the impact of technology on humans.

The Past Drives the Future

The combination of technology and society is not a new idea for Virginia Tech. Within eight years of joining the university faculty in 1971, Joseph Pitt, a professor of philosophy, had become director of Humanities, Science, and Technology, a new program for which he had helped to create the infrastructure. This soon led to the formation of the Center for the Study of Science in Society.

“Our dean at the time, Henry Bauer, wanted to establish a center whose purpose was to produce white papers dealing with the impact of scientific and technological developments upon society,” says Pitt. “We started looking at science and its tools and saw its ramifications from sociological, philosophical, and political lenses. So, we developed a program where students could decide which aspects to pursue.”

The center evolved into today’s Department of Science, Technology, and Society. One of its assistant professors, Rebecca Hester, is also a Tech for Humanity scholar specializing in equity and social disparity in the human condition. Her research interests began with the study of immigration and now encompass the social, ethical, and political implications of scientific and technological advances in biotechnology, biomedicine, and public health.

“When it comes to technology, I start with a conversation about social values,” Hester says. “We need to reflect on what it is we value and what we should make manifest in the world. That has to do with what it means to be human, who we are, what we value, and what we think we need. Then we can decide on the technology.”

She cites her research on immigration. The immediate answer to problems that arise from migration is not more surveillance technologies, such as monitoring through microchipping asylum seekers, she says. Instead, the conversation needs to define the underlying cause. Is it an immigrant problem, a perception problem, or a security problem?

“It’s not about the next greatest innovation,” she says. “It’s about doing the hard work of reflecting on the society we live in and trying to come up solutions that are meaningful, sustainable, and responsive to the needs of the many.”

In addition to her role with technology initiatives, Hester is helping the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences build programming around displacement issues. This work allows her to look at the social and political issues facing immigrants and advocate for or against technological solutions, promoting humane and fair outcomes.

“There has never been a greater need for people to be at the table who understand the social, political, cultural, and economic implications of the technologies that society is promoting,” she says. “We are shaping the next generation who will use and create technologies, people who think not just ethically, but also politically and socially about the technologies and the science that they’re doing.”

Inspiring the Future

Such initiatives are central to what the university is doing. “We teach people,” Johnson says, “and the structure of our coursework and curriculum needs to show that technology is more than a science and engineering concern. It’s a societal issue, a human issue. It encompasses the political, the economic, the cultural, the personal.”

Johnson says the university prepares students to understand that technology has wide-ranging implications that involve everyone, not just scientists.

“To be future stakeholders, students must be informed and analytically astute,” he says. “They must understand equality, social systems, power, and how the world works at an institutional level and what it means at a human level. It’s well-being not just on an individual level, but on a collective level as well. By providing a transdisciplinary and comprehensive education, we can have an important pillar in place for making technology accountable to human interests.”

Johnson cites two recent Virginia Tech programs that are creating a new generation of responsible leadership toward technology. In 2019, the Center for Humanities partnered with the Center for Human–Computer Interaction to present the workshop Algorithms That Make You Think. It brought together historians, data scientists, and community members to look at how algorithms exclude humans from the decision-making process and create unjust outcomes. The workshop explored insights on how to transform and achieve just and equitable outcomes.

“The workshop demonstrated a timely understanding of what’s at stake with technology and innovation,” Johnson says. “Technology is a tool, and if you just let it function in accord with the status quo, you’ll end up with institutionalized and inequitable problems. But if you’re intentional and deliberate about correctives, equitable outcomes, ethical standards, and being collaborative, you can

be transformative.”

Working directly with undergraduates through the Calhoun Discovery Program, a transdisciplinary program run by the Center for Higher Education Innovation that focuses attention on technical innovation and societal transformation, Johnson is optimistic about the future of technology and humanity.

“That program runs across ten different majors and we have corporate partners in private industry who contribute their time and capital,” he says. “These are business leaders who are very clear they want a future in technology and innovation that is inclusive.”

Johnson adds that having a program that is diverse and includes underrepresented students is critical because without gender, racial, ethnic, and income diversity, society will face recurring historical problems of inequity. “We need people with the perspectives, insight, and backgrounds to produce the outcomes that will benefit everyone in society,” he says. “If you want to have technology or any system that is accountable, you have to be inclusive.”

By investing in initiatives that focus on the human dimensions of innovation and by infusing technologies with insights from the humanities, Johnson says, Virginia Tech is showing its commitment to lead social institutions in addressing the big challenges that emerging technologies pose.

“Virginia Tech is preparing leaders for tomorrow, for a future not yet imagined,” he says. “We shape leaders who know that technology must be judged ultimately not by its wow factor, but by whether it contributes to a society we want to live in, one that’s for the greater good of all humanity.”

Written by Leslie King