Stolen Identities

March 3, 2019

Imagine being led to a windowless room, told to strip, and instructed to turn left, right, and center as you were photographed in the nude. And now imagine, after you’d gathered your clothes again, being handed a grade.

A range of famous people — from Hillary Clinton and George H.W. Bush to Meryl Streep, Nora Ephron, and Bob Woodward — were subjected to such photo sessions during their college orientations. In fact, the practice of taking “posture portraits” was common at many Ivy League and Seven Sisters colleges between the late 1920s and mid-1960s.

“The program was run by physical education departments under the guise of promoting good health,” says Andrea Baldwin, an assistant professor in the Virginia Tech Department of Sociology. “If your posture received a failing grade, you’d have to take a class to ‘correct’ the deficiencies of your spine. Some schools wouldn’t allow you to graduate until you passed.”

Perhaps even worse than the humiliation, Baldwin says, was the possible impetus behind the posture portraits. Driving the practice was a psychologist, William Sheldon, who believed that physique determined a person’s destiny. He used the photographs to classify people by body type.

“At best, Sheldon’s work was based on faux science,” Baldwin says. “At worst, it was motivated by eugenics. Regardless of his real intentions, underlying the practice were assumptions of what it meant to be normal.”

Baldwin learned of the diagnostic practice while a visiting assistant professor at Connecticut College, which had followed the practice earlier in its history, when it was an all-women’s institution. She teamed up with a choreographer, a computer scientist, and students to delve further into the history.

“During our research into the archives of various schools and the Smithsonian Institution, where a number of the files ended up,” says Baldwin, “we were assured the photos had all been destroyed. Yet we came across hundreds of them. We were seeing women and men in the nude without their consent; we felt complicit.”

The researchers also interviewed Connecticut College alumnae who had undergone the practice. The women, whose ages ranged from 78 to 92, all regretted their compliance, even as they were given no choice. One participant characterized the experience as “dehumanizing”; another likened it to being arrested.

Baldwin points out that the dubious practice happened to mostly privileged college students. “Imagine,” she says, “what their vulnerability suggests for those not as protected by socioeconomic class or opportunity.”

So Baldwin and her colleagues decided to stage a photo session that allowed Connecticut College students to claim their own images as a kind of therapeutic reconciliation with the past.

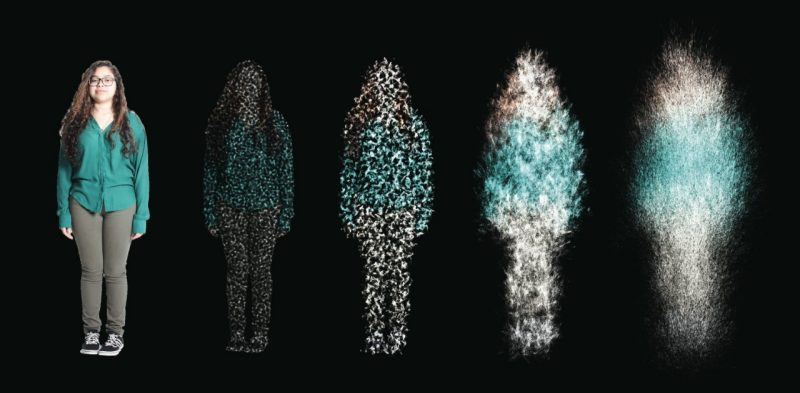

“We wanted to heal this narrative of shame by using photography, dance, and technology to refocus the gaze,” Baldwin says. “In ‘The Reminiscence’ we chose to do the opposite of everything those early photo sessions represented. Our participants wore whatever they liked and stood however they felt comfortable. The students of the past were silent; our students recorded their thoughts in their own voices.

“The past sessions sought conformity and compliance; we opted for individuality, freedom of choice, and — most significantly — consent.”

Written by Paula Byron as part of the “Missing Persons” feature in Illumination 2018–2019