Portraits of the Past

March 3, 2019

Oliver Croxton looks pensive. His light, deep-set eyes gaze to the left of the camera; his cheekbones show prominently above his dark, bushy beard. The two chevrons on his uniform sleeve reveal his corporal status.

More than 150 years after Croxton sat for his portrait, his great-great-great nephew came across it, and for Kurt Luther, the moment was electrifying.

“It was serendipity at play,” Luther says. “I happened upon a photo album of Oliver’s Union regiment in a museum exhibit. There he was in his Civil War uniform; no one in my family had ever laid eyes on him before.”

Luther, an assistant professor of both computer science and history at Virginia Tech, had long been interested in the Civil War. But now he became obsessed with offering that same thrill of discovery to others.

“It’s so powerful to look into the faces of these soldiers,” Luther says. “And yet, at most, only 30 percent of the photos of Civil War soldiers are identified. I realized we could use new technologies to help put names to faces.”

So, in 2017, Luther joined with Paul Quigley, director of the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies, and Ronald Coddington, editor of Military Images Magazine, to launch Civil War Photo Sleuth. The website uses two principal tools—facial-recognition software and crowdsourcing—to allow academics and members of the public alike to do the historical detective work.

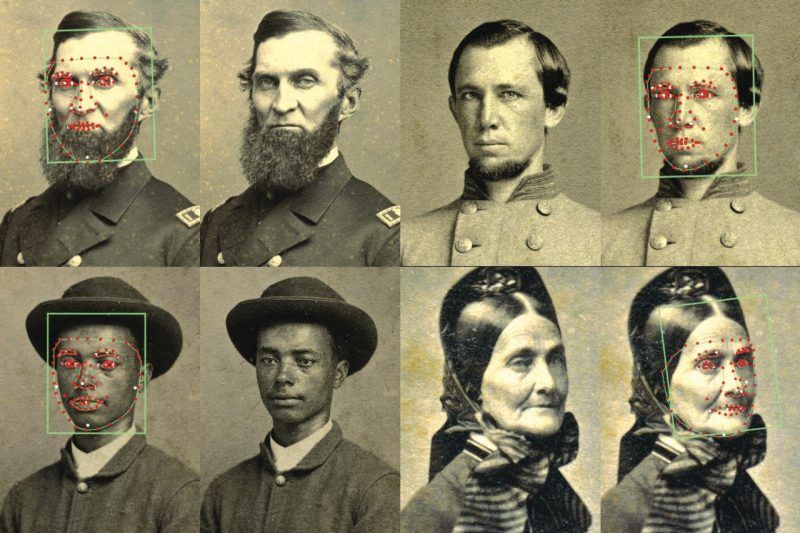

The site can scan the facial features of soldiers and compare that facial “map” with those of thousands of other images in the database. Contributors can upload photos found in attics or scattered among the online databases of historical societies, museums, and collections. The photos can then be tagged with such details as the number of chevrons on uniforms and the style of hat insignia.

“Users often search the database for photos of their ancestors or for soldiers who served in local regiments,” says Luther. “That discovery process is one of the great joys of photo sleuthing. And the site allows us to restore meaning to images and personal histories that would otherwise remain forgotten.”

Civil War Photo Sleuth now includes the photos of more than 20,000 identified soldiers, along with 5,000 others waiting to be recognized, including some civilians. More intriguing prospects are uploaded every day.

“One of the things that makes history so exciting is getting to know people from the past as people,” says Quigley, who also serves as the James I. Robertson Jr. Associate Professor of Civil War Studies in the Virginia Tech Department of History. “A photo makes a connection so much more direct. You can really imagine these people as complex human beings rather than just names in documents.”

Written by Paula Byron as part of the “Missing Persons” feature in Illumination 2018–2019