Webinar Panelist Discussion: How Do Other Food Studies Programs Work?

Webinar Series Q&A

Learning from Experience: The Food Studies Program Directors Project

As part of our Food Studies Directors Project, we invited food studies leaders from a range of institutions to be panelists in our webinar series and discuss how their food studies programs operate. They also provided written accounts of their programs' histories, events, curricula, and central lessons based on five (5) questions we posed for discussion. Their responses are below.

Panelists

Daniel Bender, Director of the Culinaria Research Centre, University of Toronto

Megan Elias, Director of the Gastronomy Program, Associate Professor, Boston University

Krishnendu Ray, Professor, Nutrition and Food Studies, New York University

Tony VanWinkle, Assistant Professor of Sustainable Food Systems, Guilford College (formerly of Sterling College)

Matthew Hoffman, Assistant Professor, Food Studies Program, University of Southern Maine

Alice Julier, Professor, Food Studies Director, Chatham University

Stephen Wooten, Associate Professor, Director of Food Studies, University of Oregon

Discussion

The Culinaria Research Centre was founded officially in 2015, with roots that stretched back a couple of more years. Ours is a research centre that supports an undergraduate minor programme in food studies and a graduate Collaborative Specialization in Food Studies (a specialization attached to a range of disciplinary programmes offered by other graduate units). Faculty in the Centre also deliver a PhD programme in food history in the Graduate Department of History.

Culinaria, as a research centre, does not hold academic lines (faculty are appointed to departments and then join Culinaria as affiliates). We currently have around 30 faculty affiliates on all three (undergraduate) campuses of the University of Toronto. (All UofT faculty (tenure stream) hold dual appointments: to an undergraduate unit which depends on which undergraduate campus, and to a unitary graduate department.)

I serve as the Director of Culinaria and have held that position since its founding.

Our program started in 1991, offering an MLA, which is now an MA. Our founders were Julia Child, Jacques Pepin and Rebecca Alssid, who was Director of Special Programs at Met College, the extension school of Boston University. Rebecca and Jacques Pepin had already initiated the Programs in Food and Wine, three years earlier to offer a culinary certificate. Together, the three decided to offer courses about food that approached it from an academic perspective—history and anthropology and literature—but it was important to keep the two approaches—hands-on and scholarship—together. Jacques Pepin taught the first Gastronomy course, which was “Culture and Cuisine: Their Rapport in Civilization.” The program grew from Pepin’s course and a course on the Anthropology of food, drawing on existing courses at BU to fill out the curriculum.

We currently have about 90 students enrolled in the program. We offer an MA and a Certificate in Food Studies. Both can be completed in person or online and students are welcome to mix modes.

Being part of Met College has meant that we are well set up to serve working people and to provide an online degree and certificate programs. Because Met has been BU’s extension school, our courses are all at night and tuition is slightly lower than that at the rest of BU. Being part of BU has enabled us to benefit from the strengths of an R1 university. Our students can take classes from divisions across the university and also at the other institutions that are part of our Boston consortium.

In terms of dialogue with and fitting with other food-related programs on campus, we consider ourselves one unit with the Programs in Food & Wine. We share space, plan courses, and cross-promote each other’s events. We have a good relationship with the Sustainability Director for BU and with the Sustainability Director for BU Dining Services. For example, we participated in a food waste audit for BU Dining. The Programs in Food & Wine also partner with our university radio station, WBUR, on a series of live-audience interviews with chefs.

The University of Southern Maine Food Studies Program began in the mind of Economics faculty member Michael Hillard, with funding support from the Maine Economic Improvement Fund.

In 2015, Hillard, with the support of a consultant, Jo D. Saffeir, began reaching out to potential academic and community partners as they set about designing the USM food studies program. Over the course of a year, they familiarized themselves with the needs of food systems actors in southern Maine; researched other food studies programs around the country; and developed a plan for how a food studies program at USM might serve the needs of students and the broader community.

Based on the plan they created, the Maine Economic Improvement Fund committed more than 2 million dollars over a 4-year period to support a program with the following goals:

· USM will graduate students with a solid academic understanding of global, national and local food systems, and with general professional skills essential to successful food-related work in the private, nonprofit and public sectors.

· USM will create strong collaborations with the local food-based business, nonprofit and public sectors to support positive social, economic and environmental impact.

· Maine residents and policymakers will understand and promote the interconnectedness of land and ocean-based food systems, with an emphasis on environmental and community sustainability.

· Maine residents and policymakers will be aware of and understand the issues related to social and environmental justice in all aspects of food systems work, including food security.

These goals were based on a program vision that continues to guide us to this day:

· Environmentally sustainable food production

· Entrepreneurship and Economic Development that supports and helps to expand local, sustainable food production (including the bounty of the Gulf of Maine)

· Supporting efforts to make the local and regional food systems to be socially responsible and just, including improved livelihoods in the food economy and ending food insecurity

· Supporting research and educating incumbent and future workers in Maine’s food system, and food-oriented nonprofits and government agencies.

In 2016 the project team hired Kristin Reynolds, a NYC-based food systems scholar to consult on curriculum design, and by the spring of 2017, the nascent program was ready to hire two full-time faculty members—myself and Jamie Picardy—to launch the program in the fall of that year.

In addition to the courses taught by Professor Picardy and myself, our course menu was filled with food-related offerings provided by faculty with affiliations throughout the university.

One of the great strengths of the program has been the diversity of disciplinary backgrounds, experiences, and personal perspectives of participating faculty, who contribute through their teaching and their service on the Food Studies Council, which is the governing body for the Program. I’ll talk more about the Program’s place in the University and its trajectory in a moment, but first let me introduce you to the main faculty members.

Michael Hillard, whom I have already mentioned as the initial force behind the Program’s creation, is a popular economics professor who has been at USM for well over 30 years. He served as the Food Studies Program Director for our first three years.

Cheryl Laz, the current Program Director, has been a member of the project team from the beginning, also serving as chair of the Sociology Department for most of this time. Prior to the founding of the Program, Prof. Laz was already teaching several food systems -related courses.

As the two most senior faculty members on the Food Studies Council, Professors Hillard and Laz—each in their own way—provided essential support to Prof. Picardy and I, who, as new-comers to the University, would never have managed to navigate the administrative bureaucracy on our own.

Another significant faculty member is Richard Bilodeau, whose presence on the council connects us to the School of Business and whose courses on food and entrepreneurship are of particular importance for many of our students. Well-networked with both the University administration and the local business community, Prof. Bilodeau’s creative energy has also made him a valuable partner for Prof. Picardy in organizing student research and events on campus.

Prof. Picardy and I are the two official Food Studies faculty members and until recently have shared primary responsibility for providing courses in the core curriculum, as well as for supervising students and carrying out community-engaged research.

Professor Picardy came to USM from the Friedman School at Tufts University, where she earned her PhD in the Agriculture, Food, and Environment Program. An award-winning educator, Prof. Picardy works with community stakeholders to integrate applied research into her courses, giving students the opportunity to understand the real-world importance of the subject matter and how they can make a difference. Students in her classes typically present the results of their work to community partners and have also published in academic journals.

I came to USM from the Centre for Rural Research in Trondheim, Norway and was previously a faculty member in the Food Studies Program at New York University. I did my graduate training in rural community development at Cornell University. I would be glad to talk about my classes, but I have been transitioning away from teaching and toward supervising groups of students on externally-funded research projects in partnership with local and regional organizations.

You may not be surprised to hear that a significant portion of the teaching in our program has been taken on by a rotating cast of extremely knowledgeable and hard-working adjunct faculty.

Jess Gerrior, who has taken over my teaching responsibilities with conspicuous talent, is weeks away from finishing her PhD in environmental studies at Antioch University in Keene, NH, where she also works with, directs, or serves on the board of several regional food systems organizations.

Lastly, I need to mention Amy Carrington, who played a crucial role in the program starting in early 2018. In addition to providing skillful administrative support, she served as our Internship Coordinator – a position of central importance to student recruitment, community engagement, and faculty research. Ms. Carrington’s years of experience with local and state-wide food systems organizations, as well as with farming, have given her the network connections, grant writing skills, and administrative abilities necessary to connect our students and faculty to the world off campus. If there is one thing that other food studies programs should copy from USM, it is to create a role like this one and to find a similarly qualified person to fill it.

At this point, I should backtrack and provide some basic information about the program. The program itself is situated in the Department of Economics and Sociology, but functions somewhat like an independent department. Our Director (currently Cheryl Laz) has a role similar to that of Department Chair and our Food Studies Council meetings are like department meetings. All of the Council members, however – with the exception of Jamie Picardy and me – also have departmental affiliations and teaching responsibilities outside of Food Studies.

The Program consists of an undergraduate minor and a graduate certificate.

The undergraduate minor has been very popular and there are also many students who take Food Studies courses without completing the minor. One way in which we have attracted non-minors to Food Studies courses is by cross-listing these courses with other programs, a practice that has proved to be a useful strategy for recruiting students into the minor, especially once they hear about the internship program (about which more shortly).

The minor consists of 18 credits. [Minor requirements linked HERE.]

The Food Studies Graduate Certificate makes an excellent complement to many graduate degree programs such as planning, policy, nutrition, or law. It may also be pursued on its own as professional enhancement by people already working these or other professions, including hospitality or the non-profit sector.

The Graduate Certificate is a 12 credit program. [Grad cert requirements linked HERE.]

From the beginning, the Food Studies Program at USM has maintained a strong commitment to community engagement, which has been expressed through public events, student projects, and faculty collaboration with local partner organizations.

In the early phases of planning the Program, Michael Hillard and Jo D. Saffeir met with numerous local stakeholders. Perhaps chief among these in the beginning were the Good Shepherd Food Bank and Preble Street, an organization that seeks to address problems of homelessness, hunger, and poverty in the Portland area.

Professor Hillard collaborated with these two organizations on a report called Hunger Pains, showing that food insecurity has increased 50% in Maine in the last 12 years, putting the state first in New England and 7th nationally – even as food insecurity for the nation as a whole has been in decline. More than 200,000 Mainers suffer from food insecurity.

For this reason, food insecurity was a major focus for the program in the first few years. In March of 2019, we hosted a large conference – the annual Universities Fighting World Hunger Summit – with over 500 student and faculty attendees from all over the country. At about the same time, we were becoming increasing aware of the high rate of food insecurity among students, both nationally and on our own campus. We already had students interning at the Preble Street resource center, and that spring we began collaborating with them and the campus food pantry to improve outreach to students in need. I’m glad to answer more questions about this later.

Professor Picardy, as I have mentioned, has made it her regular practice to have students in her classes collaborate with community partners on research projects that are tailored to meet the partner’s needs, culminating in student presentations and reports with community members in attendance. Both the students and the community partners have found this very valuable and Professor Picardy has been recognized for her excellence in service learning.

My own classes have been less research-oriented and also less community-engaged, apart from having a large number of class visitors from local organizations. My student-centered, community-engaged research has come more in the form of supervising groups of graduate research assistants and undergraduate interns on projects in cooperation with community partners. I’d be happy to talk about these during the Q&A if there is time.

The most important thing to tell you about is the internship program, which serves the dual purpose of education and community engagement, and has proven extremely valuable to students and local organizations alike. It has also been our best recruitment tool.

The internship program is funded by the Maine Economic Improvement Fund, enabling us to pay interns $14 per hour while placing them with host organizations, businesses, or agencies in the state of Maine. Internships are typically 150 hours per semester for 3 credits and can be completed either during the school year or over the summer. We have had as many as 50 interns in one year working for a wide variety of public, private, and non-profit host sites.

The internship is a highly structured learning opportunity in which students have both a host site supervisor and a faculty supervisor. Before the internship begins, students work with their faculty supervisor to create a learning plan that includes goals, activities, and final products. The interns meet as a group several times during the semester with the Internship Coordinator and at the end of the semester give an on-campus presentation to an audience of their peers, host site supervisors, and faculty members.

Many students consider this the most valuable part of their food studies experience and it is not uncommon for interns to be offered a job at their internship host site after graduation.

Chatham University was a small women’s college in Pittsburgh that transformed into a university with graduate programs, its main claim to fame being that it is the alma mater of Rachel Carson. In 2009, they were gifted a 400 acre property north of the city, which was a former country house, working farm, and retreat center for an executive from the Heinz Corporation – women who worked in the pickle factory would come to Eden Hall, as it was called, to rest, play, and escape the industrialized city. When Chatham acquired it, they decided to create a School of Sustainability and the Environment at the site and the first program to be launched was Food Studies. I was hired to design the program and be its first director and I spent about six months exploring and traveling to other programs -- beyond the ones I knew from my relationship with the Association for the Study of Food and Society (ASFS) and the Agriculture, Food, and Human Values Society (AFHVS) – especially those with student-centered farms and a liberal arts focus.

I have been in the department since 2005. I was the Chair from 2012-2021.

Four sources of NYU Food Studies; three acknowledged and one less acknowledged. This is a critical institutionalist view of our development (not a marketing one).

A. Nutrition/Public Health: emergence of obesity as a perceived social problem in high-income countries

Synergies of timing and location: NYU Food Studies developed in a Department of Nutrition, under the direction of a Public Health Nutritionist Marion Nestle (1996), by first paying attention to food in the body physiologically, then incrementally widening circles of inquiry to the social world of eating, cooking, and provisioning; first in consumption, slowly in distribution and production.

B. Rural Sociology: ASFS + AFHVS: Critique of agroindustrial development + Oldways Preservation & Exchange Trust

Sustainability – ecological + sociological critique (health of communities/concentration/ power)

A second source of NYU Food Studies was the emerging environmental critique of the agro-industrial food system from Silent Spring (1962) to The Diet for a Small Planet (1971). The import of these perspectives were developed via the intermediation of organizations such as ASFS/AFHVS/Oldways

C. Consumer Culture/Urban Foodie Cultures/Upscale Restaurants/Celebrity Chefs/Hospitality

Other disciplines in having paid attention to agricultural production and distribution (economics and agricultural science) and individual consumption (psychology, nutrition and marketing) left room for the theorization of the social. Which occupied the space of what exceeded the reach of those disciplines, such as, the aspect of food consumption that is not determined by conscious individual will, but shaped by collective action, unconscious habits, and choices framed by social structure such as class and gender. Theorists were also turning away from the “prevailing condescension” towards consumer culture from about the 1980s.

Media attention; Food Sections of NYT (Marian Burros June 19, 1996 = A New View on

Training Food Experts https://www.nytimes.com/1996/06/19/garden/a-new-view-on-training-food-experts.html)

Kitchen Confidential (2000) and Iron Chef Japan (Food Network 1994) transformed the public culture of thinking and playing with food.

NYU Food Studies is linked to its location in one of the largest media and consumer markets in the world with innovative city policies. Our success and our challenges are linked to our location in NYC which reflects both affluence and race/class inequalities, largest school lunch program, important green market, urban farming and waste-disposal initiatives, thriving food-related start-ups, and one of the largest urban healthcare systems.

Other than Nutritionists the first people to be hired at NYU Food Studies were Amy Bentley, an American historian and Jennifer Berg with training and experience in Hospitality Management at Cornell University. So the first domains of expansion were History + Hospitality. The next circle of expanding knowledge was when an Applied Economist Carolyn Dimitri and a Policy Analyst Beth Weitzman joined the full-time, in-house, faculty, to deepen attention to Systems + Policy/Advocacy. In the last round, so far, the domain was expanded to include faculty working inter-nationally on issues of globalization, immigration, and circulation of cultural practices transnationally. Nominally including Sociology + Design Thinking by way of Krishnendu Ray and Fabio Parasecoli

In addition the program depends on two dozen part-time faculty and full-time faculty in other departments such as Environmental Studies, Performance Studies, Marketing, Business, Wine Studies, Waste, and an extensive experience-based international travel program

D. Home Economics often renamed as consumer/family studies

The decoupling of food from medicine, and wellness from illness, as analytically separate realms – due to the working of the profit and prestige motives associated with what is often called professionalization of a field – led to the bifurcation of science-based biomedicine and common sense based dietetic advice. That divergence has not healed yet, but a science-based dietetics slowly emerged along with Home Economics between the 1880s and 1940s, aided in the United States by funding from the Department of Agriculture (USDA). The Morrill Act of 1862 had funded Land Grant Universities with the responsibility to foster agricultural development. Ellen Richards became one of the first female research professors to lead a newly conceived department of Home Economics at Cornell University in 1909. She added practice homes to university laboratories early in the 1910s to train young women in the science of running households. This was an optimistic era which assumed every domain of human life could eventually be mastered by a science relevant to it. Home Economics, Dietetics, and Nutrition were new and rare domains of science where women dominated. That would in itself lead to its ghettoization and marginalization as men avoided the field and women learned to circumvent its reach as new waves of feminism showed them a path away from the confinements of the home and the kitchen.

Sterling College offers undergraduates a BA in Sustainable Agriculture and Food Systems (SAFS). The degree program at Sterling is intimately linked to the college farm, which has been part of the institution since its founding in the 1950s. The farm serves as a major resource for the hands-on, experiential nature of Sterling’s program. Students might learn about the history and culture of small grain agriculture in the classroom, for example, while subsequently engaging in harvesting, threshing, milling, and baking with wheat or barley grown on the college farm. This embodied, sensory education is a hallmark of Sterling’s program.

Similarly, Sterling is one of nine federally designated work colleges, which means that all residential students are required to work under variable annual contracts, with that earnings going directly toward tuition remission. The farm and the kitchen are the two largest “employers” of students in the work program. Students in the work program go through progressions of responsibility (from entry level to management level positions) that allow them to accumulate this adjacent body of experience.

The SAFS degree is Sterling’s largest degree program by number of declared majors and graduates. Indeed, many characterize the college as a “farm school,” due to the centrality of the farm to the college’s campus and identity. This identity is further grounded in the college’s location in the Northeast Kingdom (NEK) of Vermont. The NEK is overwhelmingly rural, and has been an unlikely epicenter for local movement activity since the back to the land era of the 1960s and 70s. This history creates a great number of off-campus opportunities as well, whether through internships, field trip experiences, or in some cases, direct employment. Students also have opportunities to learn at two remote program sites—The Wendell Berry Farming Program in Port Royal, Kentucky, and The Farm Between, in Jeffersonville, Vermont.

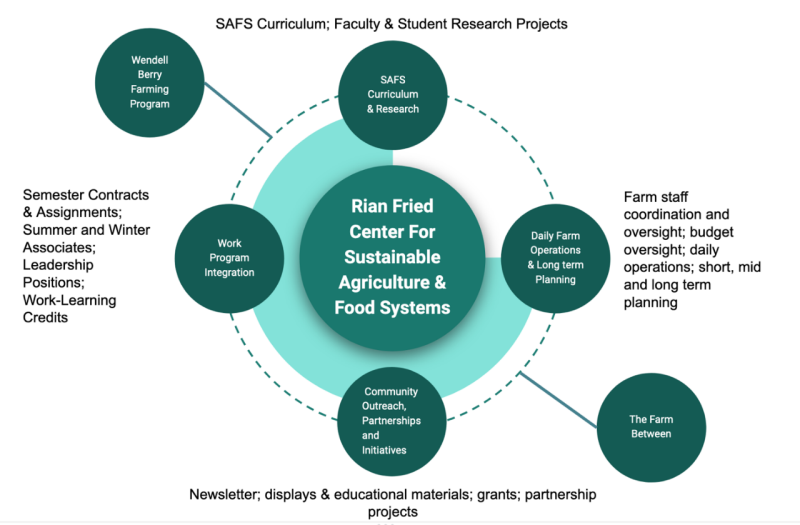

The faculty and staff affiliated with the SAFS degree include natural, agricultural, and social scientists, adjacent faculty in the environmental humanities, as well as the farm and kitchen staff. All of these elements are coordinated through the umbrella of the Rian Fried Center for Sustainable Agriculture & Food Systems (RFC).

Rian Fried Center for Sustainable Agriculture & Food Systems (RFC)

Our interdisciplinary program was inspired and fueled by an international conference on Food Sovereignty held at the UO Law School in 2011. On the heels of the conference a working group comprised of faculty, staff and students worked to create a new academic program on campus. We started in 2013 with a Graduate Specialization that could be added to any graduate degree and added a Minor for undergraduates in 2016. Both curricular enhancements were welcomed by students and are currently well established and enrolled. I am the founding Director of the program. More details can be found on our program website: https://foodstudies.uoregon.edu/

One of only a handful of university-based academic food studies programs in the country, the UO Food Studies Program is set apart by its broad interdisciplinary approach that spans the social sciences, the humanities, and the natural sciences. Founded in 2013, the Food Studies Program aims to foster the kind of in-depth research and analysis that will establish our campus as a leading player in the developing field of food studies, making the UO a center for intellectual and policy work on matters of increasing local and global significance.

The idea for the UO Food Studies Program came about in 2011 when, following an amazingly powerful Food Justice Conference at the University of Oregon’s Wayne Morse Center, more than a dozen faculty and graduate students met to discuss strategies for harnessing the momentum on our campus around food issues. It was quickly acknowledged that many of the existing food studies programs in the US focus on the fields of gastronomy, agriculture, and nutrition, while relatively few have the kind of breath and depth of expertise represented on our campus. Also in 2011, an interdisciplinary research group, Food in the Field, emerged with the support of the Center for the Study of Women in Society. The group has hosted numerous work-in-progress talks and receptions for visiting food scholars on diverse topics that spanned the globe from prehistory to the present.

Due to the broad interest in food issues among its faculty across disciplines and its core strength in the liberal arts and sciences, the University of Oregon is uniquely positioned to address the need for a truly interdisciplinary food studies program. Added to these strong academic foundations, our program is located in one of the most beautiful and productive regions of the United States. The Eugene-Springfield area, the Willamette Valley and the Pacific Northwest at large represent a tremendously rich environment for food studies and food-related livelihoods and enterprises.

With the launch in Fall 2013 of the Graduate Specialization in Food Studies and Fall 2016 of the Undergraduate Minor in Food Studies, we have established a signature program. Due to its existing and firm commitment to interdisciplinary research and teaching and its established focus on food-related themes, the Environmental Studies Program is the academic home for the Food Studies Program.

Our web blurb says it well: “The Culinaria Research Centre is the hub for Food Studies at the University of Toronto that blends research excellence with community engagement and student research experience. Our projects provide new insights into some of the major questions circulating in the field of Food Studies today, including the place of food in cultural identity and expression; the relationship between food, diaspora, and inter-ethnic/inter-cultural contact in Canada and beyond; commodity production and labour, from slavery to the age of empire to the present-day; and the links between food systems, health, gender, and family.”

We define Gastronomy as examining the role of food in historical and contemporary societies from multiple perspectives including political, cultural, experiential and entrepreneurial. We take a multi-disciplinary approach to understanding what food can tell us about human life. We emphasize the importance of bringing together hands-on and scholarly learning about food by granting students credit towards their MA for experiential classes like the culinary arts lab, wine studies and cheese studies and integrating food studies scholarship into our culinary arts training.

The Food Studies Program at USM takes a humanities approach, with emphasis on economic development, food justice, and the environment.

The program was designed to provide a holistic and applied approach to a multi-disciplinary field that was still in the early stages of its existence: The website says we “emphasize a holistic approach to food systems, from agriculture and food production to cuisines and consumption, providing intellectual and practical experience from field to table.” We wanted the approaches to history and culture that seemed central to Food Studies, but also the applied, experiential knowledge of the culinary and agricultural fields. In addition, we emphasized the community component of food systems, seeing how food insecurity, inequality, economic opportunity, and cultural meaning are all realized at the regional and local level. Social justice and equity issues are embedded in courses rather than treated as separate subject matter. For example, food systems is taught as a series of narratives about how people in social and historical groups sustained themselves: some of those narratives include colonialism, capitalism, diasporic experiences, and more.

An undergrad BS (with Nutrition, Public Health, Food Studies): about 25 each year; 200 in all; see below on the clustering of the curriculum and themes

An MA: bread and butter of the Food Studies program (admit about 50 each Fall). We have identified three major content domains (a) Policy/Advocacy; (b) Media/Cultural/Social Analysis; (c) Social Entrepreneurship (the last one driven by student interest and initiative + partnership with the Business School; small companies ventures = Dona Chai, SeeFood Media, Haven’s Kitchen, Rooted Fare, etc.)

A very small PhD program - agnostic about quantitative and qualitative; social sciences and the Humanities

Attention to skills with numbers and with writing; experience and portfolio

The Sterling College program, as a program in Sustainable Food Agriculture & Food Systems (and not “Food Studies” per se), and within a college that is defined by “ecological thinking and action,” is first and foremost concerned with socio-environmental definitions and understandings of food and agriculture. The program offers coursework in both natural and agriculture sciences (i.e., soil science) as well as social sciences/humanities (i.e., anthropology of food). As such, the program attempts to provide a wide-ranging interdisciplinary grounding in an environmentally focused agriculture and food systems program.

Besides this environmentally focused curricular orientation, the program at Sterling offers complementary reduced-credit “skills” courses often taught by adjunct instructors drawn from the broader community of practitioners in the greater community. These can range from permaculture design, to organic orchard management, to cheese and bread making. Courses in these areas are variable offerings based on instructor availability.

We define Food Studies broadly to include scholarship and education in the humanities, natural sciences, and social sciences and in professional contexts as well. Our connections and partnerships bridge into the community as well with linkages to local, regional, national and international entities and processes. While we attend to food studies within this broad frame, as the state’s flagship Arts & Sciences campus (non-land grant), our program has a focus in the humanities and social sciences.

Tough question! Insofar as we do not hold budget lines (faculty are paid by disciplinary departments: sociology, history, etc.), faculty commitment is voluntary. We have a solid core of faculty who are deeply involved and we share teaching responsibilities for the graduate programme. (Those at the Scarborough campus (UTSC), teach in the minor programme in food studies.) Community is at the heart of it all. Our faculty are an extraordinary group of people. They are productive, but, above all, collaborative, smart, enjoyable, and many other nice things. Recruiting students is less difficult. By now, there are just so many amazing students (grad and undergrad) who want training in food studies. The key question, for me, is identifying career pathways. Are we giving them employable training?

We have two full-time faculty, one Associate Professor and one Senior Lecturer. Together we teach five of the courses offered each year. The remaining five to seven courses are taught by adjunct instructors, many of whom have taught in the program for more than ten years. When opportunities to hire new faculty for new courses occur, we emphasize inclusivity in hiring, curriculum and syllabi.

We work with the college’s marketing department and Enrollment Services to promote our program through advertising, webinars, and outreach. This has resulted in significant growth in enrollments and increased diversity in our student population.

We recruit students in every way we can think of. We work with our Enrollment Services department as well as our Marketing department to find ways to introduce our program to potential students. We frequently reach out to other departments at BU to co-sponsor events. We also staff a table at the BU Farmers’ market to advertise our upcoming lectures, courses, and the field itself.

We have an assessment program in which we review student portfolios against our stated program goals. We expect to be able to make needed program changes based on these reviews. In addition, we have begun conducting annual Diversity and Inclusion audits of our syllabi, curriculum, programming, admissions and hiring. We also receive and review course evaluations each semester.

This remains an open question, as we are only beginning our fifth year and Covid has of course complicated everything. The biggest challenge that our Program faces is funding, since the generous grant from the Maine Economic Improvement Fund, on which the Program was founded, ran out in June of 2021. We had been hoping or expecting that the University would provide some level of funding to support the program, but that turned out not to be an option.

The two major results of this loss of funding are that the Internship Coordinator position has been moved to the University Career and Employment Hub, where it has been combined with another position; and one of the faculty positions (mine) has been shifted to soft money. This explains why I have shifted from teaching to supervising students on research projects.

The Maine Economic Improvement Fund continues to support our internship program. This is extremely useful to me because, by connecting interns with organizations with which I am partnering on a grant, the MEIF funding can be counted as a cash match – something that is required for the USDA grants that are currently supporting my position.

When it comes to student recruitment, the fact that we have a minor, rather than a major, means that we are unlikely to attract students to the University on account of our Program – something that may factor into the University’s willingness or ability to provide support. Most of our recruitment, in other words, is internal.

The Graduate Certificate, on the other hand, does attract students and, so long as we have a critical mass of students and can maintain the course offerings, I strongly believe that the opportunity to combine a Graduate Certificate in Food Studies with such degree programs as business, law, nutrition, and especially policy and planning will attract graduate students to the University.

So, in 2010, we launched the Masters’ in Food Studies (MAFS) with a first cohort of 28 people and have had cohorts of 15-30 students every year since. In 2015, we added a dual degree MAFS/ MBA. In 2021, we decided to finally start a Bachelors in Food Studies (BAFS) and a minor (although the Bachelors in Sustainability has had a food systems track for a while). These programs are still small, with the average course have an enrollment being between 14-20 people.

The MA program core curriculum includes:

· Food Systems (Equity)

• Food Access (Sovereignty)

• Agroecology (Applied Pedagogy)

• Sustainable Gastronomy (Practice)

• Research Methods (Critical Thinking)

• Thesis

• Internship

The BA program includes:

· Food systems

· Food policy and access

· Agroecology

· International Cuisine

· Global Food Cultures (history)

· Nutrition and Basic Food Science

· Business Basics and Project Management

· Other applied classes like Tree Care, Aquaculture, Horticulture, and Soil Science.

· A junior year immersive program in Sustainable Production from Agriculture to Culinary, along with depth in Community and Nutrition.

· An internship and a capstone project

Content areas in both programs include: Writing and communication; Markets, business, and entrepreneurship; Equity and social justice; Labor; Policy, politics, and community; Pedagogy and curriculum development; Agricultural and culinary practice in historical context.

Essential to keep cost under control; fund-raising linked to affordability for students; maintaining adequate student interest (social media presence); recruiting new hires with expanding field (especially about racial inequalities; global inequalities; agroecology; consumer psychology; ethics)

Relating Strategic to Tactical stuff: Repeated explaining to every Deans’ team – agile Chair and Program Directors – how we are cutting edge on sustainability, social justice, animal welfare, student interest (food is the new music). I have worked with 4 Deans’ teams in 15 years: the task is to understand every Dean’s strategic vision and relate it to Food Studies (Sustainability; Community; University of the City and in the City; Social Justice – access and equity)

Partnership with Nutrition and Public Health (gives us gravitas)

Partnership with the Media world (gives us coolness)

Urban Farm, Food Lab…. allows us to calibrate the challenges of urban sustainability on a very small scale; generates a lot of media attention (as we are in NYC); and allows us an opportunity to offer community service

Drawing attention to strategically important grants, publications of all faculty, alumni placement, media attention (without over-crowding and noise), company creation, most interesting courses, etc.

Challenges: cost and affordability (which is also linked to our location in NYC)

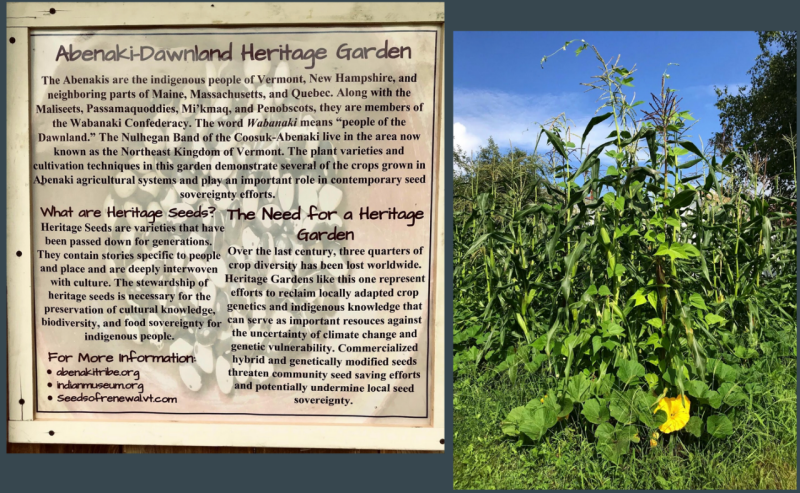

As mentioned above, the SAFS degree is the most popular at Sterling. It tends to have a steady stream of student interest, but this is often supplemented with active outreach efforts. The RFC published a quarterly newsletter, for example, that provided an outlet for faculty, staff, and student work and thought related to SAFS. Through the aegis of the RFC, partner projects were initiated with the Nulhegan Band of the Abenaki Nation, the University of Vermont, the Huertas Project (a farmworker food security project), Migrant Justice, the Center for an Agricultural Economy, among others. These partnership projects created additional outlets for faculty and staff interest, thereby maintaining morale and motivation, they increased the visibility of the program, while also providing invaluable opportunities to direct student interest.

Student recruitment occurs through a combination of efforts. These include a very active social media presence, and regular tabling at conferences and events likely to be attractive to prospective students. These include regular presence (both tabling and presenting) at the annual conferences of the Northeast Organic Farming Association, and other events like the Common Ground Fair in Unity, Maine.

Our program does regular outreach to students through graduate and undergraduate level advising and classroom pitches. We utilize our broad faculty base (65+) to identify and recruit new faculty members as they join our institution.

Not a tough question! Toronto is North America’s second-largest food employment/business hub and most of the businesses are small-scale, often family. Scarborough, the part of the city where the Centre (and its kitchen) are physically housed, is one of the largest migrant and refugee destinations in the world and has a quite substantial Indigenous population. All the key ideas that food studies stresses about health, identity, politics, and justice are expressed, debated, and brilliantly articulated by and in nearby communities. Community-based, community-supportive teaching, learning, and research is central to what we do. We maintain dozens of partnerships with local organizations, mostly BIPOC led, focused on issues from healthy school lunches to community agriculture to food security to women’s food employment. In fact, in just a few weeks, a community organization called CaterToronto and Culinaria are opening a new community “food learning and innovation place,” a food hall, incubator, and education centre funded and built for our use by the City of Toronto. On campus, it is fair to say that while we still often confront the “food is fun” or “teach paragraphs not pizza” nonsense, food is increasingly noted. After all, UTSC has begun a massive campaign of edible campus planting focused on native foods and based on Indigenous food knowledges and has started a 10-acre campus farm. One of the big challenges, it is fair to say, is how to build a centre and a programme that can encompass approaches from food culture to agro-ecology. As yet…unsolved.

Together with the Programs in Food & Wine, we have a history of providing our community with interesting events about food, featuring scholars and chefs, lectures, discussions and feasts. We have received internal and external grants to support research and events and we have worked with groups in our community on programming. We receive funding from the Pepin Family Foundation to support a lecture series and the Julia Child Foundation supports a student writing award every year. In addition we received a gift to establish the Gastronomy Fund, which supports students presenting at conferences, helps fund some student run-events and, when the pandemic recedes, will support a visiting scholar to work conduct research in our culinary collection.

I think this has mostly been answered above, but to summarize: course offerings, public programming, the internship program, and community engaged research make the Food Studies Program a valuable asset to both the campus and the broader community.

Prof. Picardy’s class-based research has contributed to waste reduction on campus and to the increased use of local seafood in the cafeteria; Ms. Carrington and I have collaborated with campus and community partners in an effort to address student food insecurity; and a large number of student interns have worked with local and regional organizations on a wide variety of issues of concern to the community at large.

We place a strong emphasis on learning-by-doing and experiential learning – for the graduate program, this includes courses that span both applied and subject overview, like Dairy, Sustainable Meat, Grains, Fermentation; Wines, Cider, Mead, Urban Agriculture, Tree Care, and Aquaculture. We also try to teach a range of methods.

The staffing of the program is tight: there are five full time faculty (as of 2016) in the department and many affiliated faculty in programs such as: Sustainability, English, Business, Biology, Environmental Science, Occupational Therapy, and Exercise Science. We have only a few adjuncts who have taught with us, many of whom have been there for over eight years in writing, GIS, soil science, and food science. The agriculture on campus is staffed by a farm manager and on and off, a director of sustainable agriculture who is also faculty (one retired and it took us a number of years to be granted a replacement). We are in the process of hiring a director of culinary and food production. CRAFT, the Center for Regional Agriculture, Food and Transformation, has four full time staff members, who support students through research and outreach projects but also teach one class per year.

Urban Farm = green space for community

Food Lab = cooking classes for student groups

Community health = with the help of nutrition and dietetic students and faculty; equity and social justice; under-served communities; environmental racism; access to good food, especially fresh fruits and vegetables at affordable prices; SNAP acceptance at Farmers Market; advocacy work with immigrant street vendors; changing laws on vending in the City; healthy eating initiatives with African-American churches in Harlem

Iron Chef Dysphagia = working with medical school and allied health on swallowing disorders

Social entrepreneurship initiatives = jobs opportunities for the under-served; racial and gender equity foregrounded

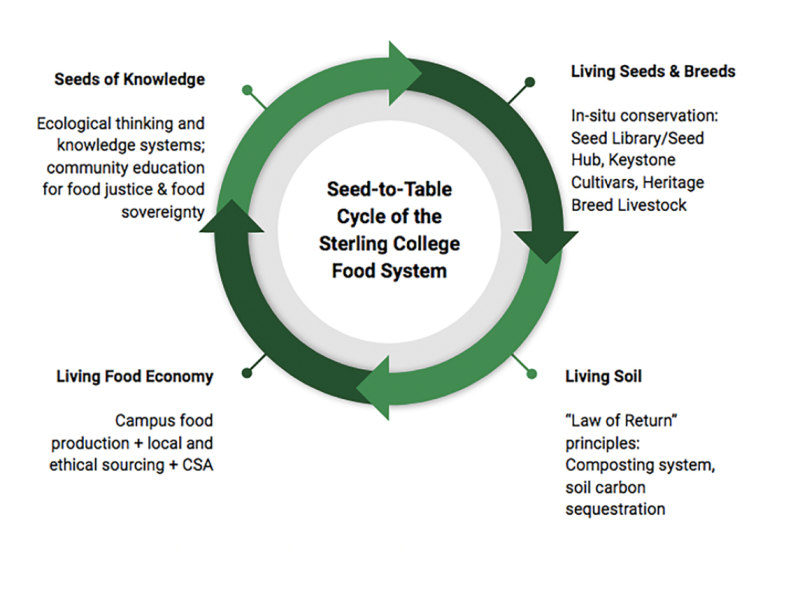

The SAFS program is integral to the Sterling campus community. Through integration with the farm and kitchen, the SAFS program provides food (in form of both raw ingredients and prepared dishes) for our community, and through closed-loop management, also provides campus-generated fertility for the farm operation through composting operations. In addition to on-campus contributions, the farm offers an annual Community Supported Agriculture program for the immediate community. As of the 2020 season, the CSA included subsidized shares and ability to accept EBT, to expand to accessibility of the program. The seed-to-table diagram below illustrates the various dimensions of the program’s deep integration.

Seed-to-table Diagram

Our Food Talks Series is the main venue for reaching the campus and local community with food studies related programs.

Beyond the community-based approach, our public events series is very important. We’ve held almost 200 events in the last five years and often look to co-sponsor with other units, organizations, etc. We find that untraditional formats tend to excite more than ‘book tour talks’ (for example). We often give visitors the chance to run an additional session in our kitchen. The kitchen is an essential place for us for teaching, research, community engagement, eating together, gathering — everything. Our connections to publishing (the Culinaria book series at University of Toronto Press, Gastronomica, and Global Food History) are vital as well, not least for the opportunities they provide to grad students. Finally, the postdoctoral programme is a pillar of the Centre. Every year, they bring fresh energy and new ideas.

Most recently, students in Gastronomy have won internal Boston University funding competitions to host events that bring together Food Studies themes and work on inclusion and equity. One was about the exclusive nature of wine studies and the other was about foraging and gentrification. These events were open to the public and well-attended by people from the BU community and beyond. It is very fulfilling to see our students imagine, propose, win funding for and enact these exciting conversations.

Our program’s most unique feature is the experiential element. Having an excellent culinary arts program as our sibling program enables our students to understand how deeply connected material and intellectual understanding of food are.

Follow us on Instagram! @gastronomyatbu Read our blog! Listen to our podcast!

Our largest program by far was hosting the annual Universities Fighting World Hunger summit, which attracted over 500 students, faculty, and nonprofit staff from all over the U.S., as well as other countries. We have also hosted a variety of nationally-recognized speakers for public events. All of the faculty attempt to tie such events to their courses when possible. In the case of the hunger conference, a sizeable number of student interns were involved, at least one of which was offered a job afterward, based on her excellent performance in putting together locally-sourced meals. It is also a common practice for faculty to invite guest speakers to their classes and, during the first three years, the Program made a certain amount of money available for this purpose. I especially took advantage of this opportunity, bringing as many community food systems stakeholders as possible into the classroom, sometimes organizing panel discussions, and always on these occasions opening the doors to the wider campus community.

I would like to invite people to ask me any questions they might have about the Food Studies Program at the University of Southern Maine and I will try my best to answer them. You are welcome to reach out by email and in that case I can also put you in touch with other faculty members, including our Director and former Director, who may be able to do a better job answering certain questions. I am also happy to share various printed materials, such as the menu of course offerings or my own syllabi.

Community engagement is a big part of Falk programs but we have made the deliberate decision to focus on depth rather than breadth of partnerships – so we have worked consistently and across programs with the Oasis Bible Center, which is a predominantly Black community group with an urban farm, aquaculture, community café, and youth training programs, all of which are connected to various people and courses in the Falk school. We also work with a number of workforce development organizations (share culinary training classes with them and grants), farms (one of our faculty members facilitates a biointensive market garden research group with 10 farms, most of which are urban or run by farmers from underrepresented groups). CRAFT has a ton of examples on its website of its local and national partnerships, including regional grain alliances, food hub feasibility studies, and more.

· Allyship events within the university such as the Colloquium Feast/Famine that drew in supporters and softened competitors; monthly events

· Translation of what the emerging field implies for bigger issues such as sustainable development; urban inequalities; racial justice to outsiders = Dean’s Team; development opportunities

· Provide evidence of durable student interest (application numbers)

· Strong media presence (Tweets, IG)

· Agile response to emerging and acute issues

· Intensive fund-raising for affordability and equity (scholarships)

One of my personal highlights from my time at Sterling was our seed conservation and rematriation partnership with the Nulhegan Band of the Abenaki Nation. Through this partnership, realized through the Abenaki-Dawnland Heritage Garden project, Sterling college faculty, staff, and students worked with Abenaki tribal partners to preserve and recirculate Abenaki seed and plant diversity and associated cultural knowledge and histories. This effort resulted in the enrichment of agricultural education opportunities for Sterling College students and provided a forum for meaningful interactions with tribal partners. In addition to the immediate goals of this partnership, it also generated great interest among students in seed systems work, and resulted in many adjacent partnership projects, including a regional seed systems research project with colleagues at the University of Vermont.

Regional seed systems research project flyer | University of Vermont

The Food Talks, even in throughout the pandemic, have been well attended and have generated a lot of interest. During COVID we used Zoom as our meeting platform and had lots of new participants from across the globe. See our events page: https://foodstudies.uoregon.edu/news-events/

Webinars

Panel 1 is hosted by the Virginia Tech Food Studies Program, with the support of a Humanities Connections grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) It took place on October 8, 2021, and featured Alice Julier (Chatham University) and Daniel Bender (University of Toronto).

Panel 2 is hosted by the Virginia Tech Food Studies Program, with the support of a Humanities Connections grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) It took place on October 21, 2021, and featured Megan Elias (Boston University) and Matthew Hoffman (University of Southern Maine).

Panel 3 is hosted by the Virginia Tech Food Studies Program, with the support of a Humanities Connections grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) It took place on April 1, 2022, and featured Krishnendu Ray (NYU), Stephen Wooten (University of Oregon), and Tony VanWinkle (Guilford College).