BLACKSBURG — Kurt Luther is linking today’s computer science to the technology of the 1860s.

The Virginia Tech computer science professor is the creator of the Civil War Photo Sleuth, a publicly available digital home of Civil War era portraits for soldiers and sailors who served. The website uses online crowd intelligence and facial recognition to identify individuals in pictures. Such recognition helps in cases where the individual’s identity was previously unknown.

Operating on a Wikipedia-style model, the site was launched in August 2018 and features 25,000 portraits that those using the aid of facial recognition have worked to identify and verify.

“These photos were the social media of the 1860s,” Luther said.

The site is valuable for historians, said Paul Quigley, a Virginia Tech history professor and director of the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies.

Luther’s work adds facial recognition to a growing list of technologies, including GIS data and text mining, which aid historians in learning more about the past.

“There’s nothing that compares to seeing a real person and looking into their eyes,” Quigley said. “You start to get to know them.

“It’s creating a human connection.”

A personal quest

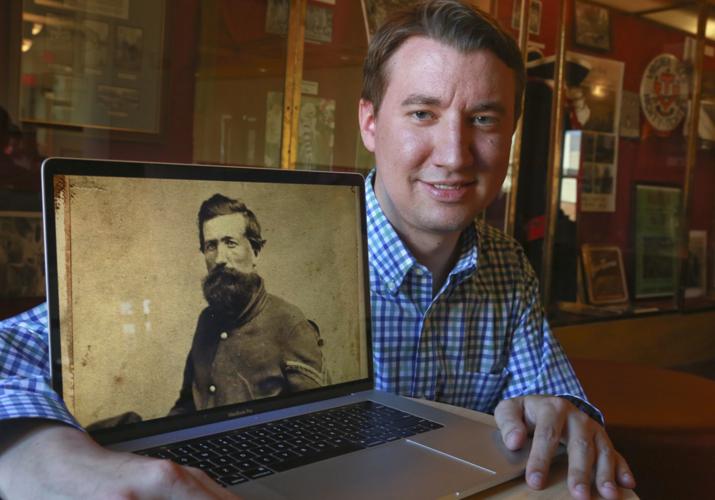

Luther has a special attachment to Photo 23897 on Civil War Photo Sleuth. The subject of the picture is Oliver Croxton, a great-great-great uncle of Luther’s, who fought in the Union Army during the Civil War.

Croxton’s portrait served as the initial inspiration for the site.

Luther first came across the portrait during a 2013 visit to a history museum in Pennsylvania, near where he grew up. Luther was aware at the time of his family tie to Croxton.

Luther bears resemblance to Croxton — minus a bushy beard. Peering into Croxton’s eyes created an instant connection, Luther said.

Looking at other photos of unidentified soldiers and sailors inspired Luther to make that connection for others, he said. People don’t necessarily need a family member, but identifying people from the past can be rewarding.

And there are plenty of photos out there.

The Civil War was a popular time for portraits, Quigley said. Many Union soldiers had their photograph taken as the technology was affordable and they anticipated separation from their families for a long time, so leaving behind a memento made sense.

Confederate soldiers rarely had photos taken because of a lack of resources in the South over the course of the war, Quigley said.

Initially Luther put 17,000 photos from public sources into the site when it launched. Since then, users have added about 8,000 photos of their own identifying ones they can and using the facial recognition software and help from others to fill in gaps, Luther said.

Technology and detective work

Vikram Mohanty wasn’t too familiar with the American Civil War. A native of India, the Tech computer science graduate student said he read a little bit about the war but it wasn’t a major focus of his studies.

Now Mohanty, who is heavily involved in the Civil War Photo Sleuth project, feels a special connection to the people who lived through that time period and the ones who presently work to understand it. It’s also altered how he looks at internet users and “real human-computer interaction,” he said.

“This project has changed the way I look at computer science,” Mohanty said. “It is history matched with the future.”

The human connection and the realization of what computers can accomplish for bringing people together has been powerful, he said.

Luther credits Mohanty, graduate student Sneha Mehta and undergraduate David Thames, with much of the project’s early success. Ron Coddington, editor and publisher of “Military Images” magazine has also helped build the site.

Major credit, too, belongs to the more than 4,000 users who’ve added photos and helped identify the subjects of portraits, Luther said.

The flashiness of the facial recognition used in the project often gets publicity, Luther said.

And it probably should. More than 85 percent of proposed identifications were “probably or definitely correct,” according to an early analysis by Luther and his students of the site.

But Luther, who is also director of Tech’s Crowd Intelligence Lab, said he’s most impressed with how users interact and improve the site.

Civil War Sleuth puts the onus on the user to confirm the identity of a photograph with the help of facial recognition. Other users can then review work in a model that works like Wikipedia, he said.

“Wisdom of the crowd,” leads to more accurate identifications, Luther said.

As people upload more photos that are identified they’re increasing the chances either photos that hadn’t previously identified can be — or unknown portraits in the future will have their identities revealed by pictures previously uploaded to Civil War Sleuth.

“It’s fundamentally a crowdsourcing project,” Luther said. “Everything you do has the potential to benefit other users in the future.”

Scholars estimate about four million portraits like the ones on Civil War Sleuth are out there.

Where those portraits might be is impossible to know, Luther said. And even though 25,000 is a tiny fraction of the photos in existence, he hopes to keep adding portraits and identifying unknown subjects for years to come.

“We have a ways to go,” Luther said with a laugh. But, “the goal is to identify every portrait of soldier or sailor from the Civil War era.”