After sojourning to the East Coast to visit the Gotham Center’s Gotham blog last week, we now travel to capital of the Midwest, Chicago, where LaDale Winling and others have embarked on an ambitious project that combines political science, history and GIS mapping to create the Chicago Elections Project (CEP). Winling, who has both a new book out, Building the Ivory Tower, and worked on the very successful Mapping Inequality project, sat down to discuss the roots of the CEP, the challenges faced in putting it together, and what makes Chicago such a worthwhile case study for urban political history.

This is the fourth in our Digital Summer School series, including the aforementioned Gotham blog, the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee, and Tropics of Meta.

Why did you establish this digital project and who is your audience?

In the summer of 2017, I was doing some research on Oscar DePriest and Arthur Mitchell, the first two black Congressmen from a northern district, DePriest as a Republican and Mitchell, a Democrat. Devin Hunter, a fellow Chicago historian, told me that the Chicago Public Library held detailed election results for their two head-to-head elections in one of their collections, so I went to check it out.

The Harold Washington Library of the CPL has nearly a hundred thousand “aperture” microfilm cards of detailed election results, down to the precinct level, going back to 1886. They have data for municipal, state, and federal elections and primaries, as well as the precinct and ward boundary maps to go with them. It was exciting and nearly overwhelming to find such a treasure trove of material on urban political history. It was also extremely frustrating to wrestle with the microfilm reader and squint at the faint and grainy data in negative on the screen. Through social media inquiries, I heard from a few historians that they had used this collection before, with some of the same difficulties, and the wheels in my mind began to turn. Margaret Garb at Washington University had used this collection in her recent book Freedom’s Ballot on black politics in Chicago. Also, Richard Anderson, who is just completing his PhD at Princeton University, had digitized some elections for his dissertation on post-WWII Chicago politics, called ‘The City That Worked.”

One of my fundamental ideas as a digital historian is that there is value in providing access to data, something I saw, for example, when a group of my collaborators made the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation redlining maps available through Mapping Inequality. Since there was established demand for these election results, I thought there would be opportunities to broaden access and simply make it easier for people to conduct the research they were already doing.

Finally, I want to emphasize that elections matter. Studying these popular expressions of political sentiment is an important way of understanding social change. My suspicion is that we often rely on qualitative explanations and narratives for political change without drawing on the messy data where voters express their actual choices.

In terms of audience, we want to provide for scholars, to reach journalists, and to connect with the public at large. Chicago historians and urban political historians who have already been using the microfilm will get better, easier access. Chicago journalists will be able to draw on this material for data visualization and to craft more detailed and meaningful stories about Chicago politics that go beyond the typical mayoral narratives. Chicagoans interested in the history of their city, their ward, their precinct, or their neighborhood will find something about the history of their communities. Chicago loves to talk politics and this will help us do it better.

Why Chicago?

Chicago has been a well-studied center of urban sociology and urban politics that, through the tradition of scholarship coming out of the many Chicago universities, has strongly shaped the way we think about urban history. By taking this new look at Chicago, we can enable an interesting set of inquiries about neighborhoods, political figures, and policymaking that can be a model for other cities around the country.

I also lived in metro Chicago (Evanston) for several years in graduate school and studied the University of Chicago and surrounding for a chapter in my book, Building the Ivory Tower. It is a place I return to for archival research each year, so Chicago also makes sense for me logistically.

How does GIS contribute to a data-rich effort like the Chicago Elections Project and what do you hope people will take away from this?

We’re in the early stages, but when we launch, I envision this project as a comprehensive data resource for Chicago political history – one where users can appreciate the multitude of Chicago political figures, the fine-grained geography of city neighborhoods, and the interaction between space and politics. We live our lives in space, build community in space, and spatial relations structure our politics, whether it be racial segregation, the provision of civic infrastructure, or other investments. So we’d like people to appreciate the historical importance of counting votes, getting out the vote, of targeting appeals to specific neighborhoods and demographics. We recognize all of these things in contemporary political campaigns and elections, but they are hard to reconstruct and do justice to in historical research. Digital data management and mapping technologies help us handle this type of research.

Through a project like this we can also teach history students and research assistants digital skills in the course of building the site and collections. History students learn GIS, HTML coding, image editing, digital archiving, and data management by working on some pieces of a larger digital project as part of their college or grad school experiences. They can go on and apply these skills to their own research or to their career work after graduation.

This project is in its early stages. What obstacles do you face?

Building any new collaboration brings questions and challenges – how much time people can devote to the project, whether we have compatible interests and visions, how we can accumulate the resources to pull it off – and that takes time to negotiate and navigate. There is a set of supportive participants and advisors with interests in Chicago politics (Richard Anderson, Margaret Garb, Brad Hunt, Nora Krinitsky, Christopher Manning, and Christopher Reed, in addition to me), which has been a great help, and we would always welcome additional collaborators.

We next would like to find an institutional home for the project that is publicly engaged with the city of Chicago. Chicago Public Library administrators have not yet agreed to host this as a digital project. It takes a while to reorient institutional priorities and we’re working to get the library to take this project seriously. Some of the staff has been very cooperative in facilitating the digitization phase of the Chicago Elections Project, but we’re just at the start of a long process. Scanning; data entry, checking, and cleaning; creating relational databases; and drawing digital maps in ArcGIS all take a long time and a lot of labor.

Where do you hope it goes in the future?

The ambition is to catalyze a data-enabled, spatially-informed way of approaching urban political history, so building relationships with scholars in other cities could help start that process and demonstrate the possibilities elsewhere. I have just started conversations with a library in New York City that also has a large collection of elections data somewhat like Chicago’s, which may be the first step.

The career of Barack Obama prompted several projects examining Chicago politics, from the Making Obama podcast to David Garrow’s book, Rising Star, and Gary Rivlin’s book on Harold Washington, Fire on the Prairie. What does this project have to contribute to our understanding of the already well-trod topic of Chicago politics?

All of those very good projects rely on narratives that are fairly triumphant about racial dynamics – either voters’ acceptance of African American candidates or black elected officials’ skillful navigation of racial politics.

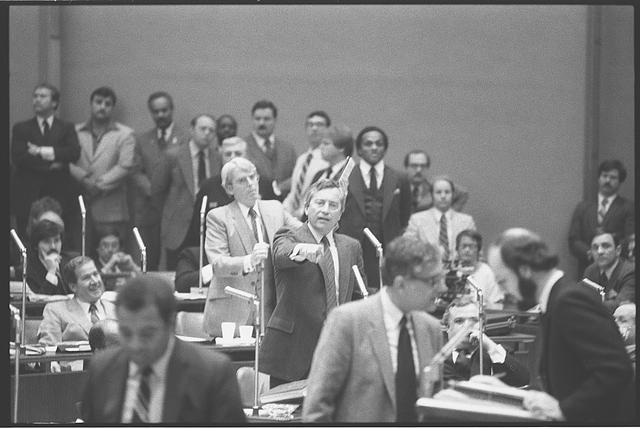

David Axelrod, who worked for both Harold Washington and Barack Obama, tells a tale about how Harold Washington’s mayoral tenure helped pave the way for Barack Obama’s rise. It’s a neat story, and he illustrates it by saying on election night for the Senate primary in 2004, Axelrod checked a northwest side precinct where Washington had faced protests and white opposition. Washington lost the precinct, 10 to 1, but in 2004, Obama carried the precinct. Axelrod’s takeaway is that Chicago grew more tolerant, even in its most regressive neighborhoods, because of Harold Washington.

It’s not as tidy as that. Groups like the “lakefront liberals,” who were supposedly strong supporters of Washington, voted for his opponents, in many precincts, by large majorities. Northwest side precincts were changed as much by demographic transition as by any changes in hearts and minds, and this spatial and voting data helps us investigate that in detail.

So this project can help scholars bring together comprehensive data resources with excellent, synthetic scholarship. The combination of data and narrative can help us enrich the stories that we tell, improve our arguments, and help us appreciate both the optimism and the failures of our very messy democratic process.

Featured image (at top): Chicago silhouette, Chicago, Illinois, photograph by Carol M. Highsmith, between 1980 and 2006, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

LaDale Winling is an associate professor of history at Virginia Tech, where he teaches U.S. urban history, digital history, and public history. He is one of the co-creators of ‘Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America’ and a forthcoming project on U.S. Congressional elections, both part of the American Panorama digital atlas from the Digital Scholarship Lab at the University of Richmond. His book on universities and urban politics, Building the Ivory Tower: Universities and Metropolitan Development in the Twentieth Century, was published by the University of Pennsylvania Press in 2017.

LaDale Winling is an associate professor of history at Virginia Tech, where he teaches U.S. urban history, digital history, and public history. He is one of the co-creators of ‘Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America’ and a forthcoming project on U.S. Congressional elections, both part of the American Panorama digital atlas from the Digital Scholarship Lab at the University of Richmond. His book on universities and urban politics, Building the Ivory Tower: Universities and Metropolitan Development in the Twentieth Century, was published by the University of Pennsylvania Press in 2017.